Revisiting Pandemicism: On the Concept of “Measures”

How often did we hear of “measures” being implemented for Covid-19?

Why the use of the word “measures” during the pandemic? What does the term mean? What was the purpose of saying “measures”?

Etymologically, “measure” has two distinct original meanings: one was meant to suggest moderation, and the other involved treatment as in “to mete out,” similar to punishing someone. It is in this second sense that “measure” came to be used in legislative and punitive terms, during the last 500 years.

One of the little words that stood out for me during the time that governments reacted to Covid-19, was “measures”. It seemed so...measured, as in moderate, tempered, rational. During that period, I lived in Quebec, and the premier of the province, François Legault, and most of the public health officials and relevant provincial ministers constantly used this word, “measures”. Though many of us have by now been trained to look out for euphemisms in government policy announcements—“collateral damage,” “kinetic response,” “headwinds,” among many others—I have not seen anyone writing about the recurrence of “measures”. Yet, for me, it was an ominous term that brought back to mind some distant, grim times in human history.

Legault’s Quebec: Public Health Measures

Premier François Legault consistently used the term “measures” in his public announcements regarding Quebec’s Covid-19 mitigation policy, as did the media’s coverage. In one press conference, he used the term 24 times. “Measures” involved various restrictions and impositions, implemented as “public health” policies. “Measures” referred to restrictions on gatherings (or the size of gatherings, their location, and the origin of participants—from the same home, the same neighbourhood, etc.); closures of businesses deemed “non-essential,” which he considered to be businesses like bars, restaurants, gyms, theatres, and concert halls; nighttime curfews; school closures, and, the vaccine passport system. General “lockdown measures” featured prominently in his press conferences. In each case, Legault spoke of “measures,” and in his usual ominous and threatening manner, promised even more “measures” should the current “measures” not meet their “targets”. The word “measures” was central to his communication strategy, as any sampling of Canadian and Quebecois media from the time will substantiate.

In the United States, the federal government used a more militarized variation: “countermeasures”. I had never before heard of “vaccines” being called “countermeasures”. To be frank, the only times I had ever heard of the use of “countermeasures,” was in movies featuring submarines during warfare, launching “countermeasures” to misdirect incoming torpedoes, or to thwart other attacks from above.

Nazi Germany: Public Health and Security Measures

Having read documents and histories of racial and medical policies enacted in Nazi Germany, I was aware of how the term “measures” was one of the favourites of Nazi officials, a recurring euphemism meant to dress up extreme behaviour. This normalization, sanitization, and rationalization of oppression and coercion is part of what Hannah Arendt described as “the banality of evil,” which helped to soften minds and get them accustomed to taking for granted increasingly extreme actions.

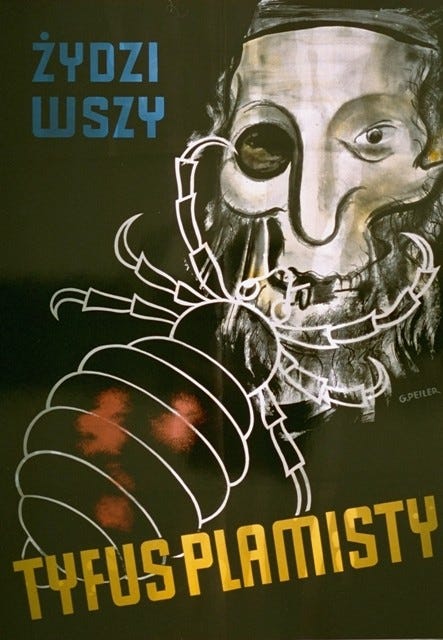

The Nazi regime in Germany, which lasted from 1933 until 1945, produced ample documentary evidence of its extensive use of bureaucratic euphemisms in policy documents and other official propaganda. (In the not-too-distant future, I will have much more to say about medicine and Nazi anthropology.) The purpose of the euphemisms appears to have been to sanitize and normalize atrocities, including racial discrimination, medical experimentation, deportion, and genocide. Even “concentration camp” was a euphemism for extermination camps. Thus the German term, “Maßnahme” (“measure”) recurs frequently as it was used to refer to coercive actions. The frequent use of the term suggests the need for a neutral-sounding descriptor for oppressive and violent actions, particularly against Jews (who were also framed as spreaders of deadly diseases). Such usage helped to maintain a veneer of legality and rationality.

Policies that made discrimination official, frequently referred to the actions as “measures,” again presumably to depersonalize and frame them as necessary administrative requirements. The Nuremberg Laws of 1935 were thus presented as “measures for the protection of German blood and honour”. The regulation of marriages and citizenship, which involved stripping German Jews of their rights, appear in documents of the Ministry of the Interior as “racial measures” (“Rassenschutzmaßnahmen”). The policy of Aryanization (involving the seizure of Jewish property) was described in memos of the Economic Ministry as “restructuring measures” (“Umstrukturierungsmaßnahmen”)—the English phrase is still in widespread use in the business world and in the pronouncements of economists employed by governments and international organizations.

Joseph Goebbels’ Ministry of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda, softened German audiences and built public tolerance for acts of increased barbarity, by referring to them as “protective measures against Jewish influence”. The April 1, 1933, nationwide boycott of Jewish businesses was announced as an “immediate measure” (“sofortige Maßnahme”) in Goebbels’ propaganda.

The Enabling Act of 1933 opened the door to indefinite detention in camps by framing this as part of a range of “security measures” (Schutzmaßnahmen). Gestapo reports from 1933–1934 frequently used “Maßnahmen” to justify arresting and detaining political opponents, Jews, among others, as was revealed by internal SS correspondence analyzed during the post-war Nuremberg Trials. In countries occupied by the Nazis, drafting subjects into forced labour was referred to as “recruitment measures” (“Werbemaßnahmen”).

No matter how intense, sweeping, or hideously violent Nazi violations would become, the word “measure” or “measures” always appeared. The forcible removal of German Jews into ghettos and camps were referred to as “evacuation measures” or “resettlement measures” (“Umsiedlungsmaßnahmen”). Heinrich Himmler’s 1943 Posen speeches pointed to “drastic measures” (“drastische Maßnahmen”) against Jews. The 1942 Wannsee Conference minutes spoke of “emigration measures” as a first step toward mass extermination. The policy of annihilating Jews was referred to as “extermination measures” (“Ausrottungsmaßnahmen”)—hardly a euphemism at that point. Historians have uncovered over 100 uses of the term “Maßnahme” in Einsatzgruppen reports on German mass killings in Eastern Europe, framing them as operational “measures”. In 1939 the Health Ministry classed the mass killing of disabled people as “measures for the relief of the population” (“Maßnahmen zur Entlastung der Bevölkerung”).

The German Jewish linguist, Victor Klemperer, documented in this 1947 text, LTI – Lingua Tertii Imperii (The Language of the Third Reich: A Philologist’s Notebook), how “Maßnahme” became a standard euphemism deployed by the Nazi regime, again apparently in an effort to dilute moral responsibility.

Why “Measures”?

This sort of terminology is meant to convey that there is a consistent, rational approach, where government actions are framed as deliberate, systematic, necessary, and proportionate responses. Such a framing prevents a soft audience (one that lacks training or a predisposition to filter and criticize) from seeing any form of excess or arbitrariness. Imposing a tax on the unvaccinated? How is that a rational and proportionate response to stopping the spread of a virus that was spread by both the vaccinated and unvaccinated? What does a curfew have to do with stopping the spread of an aerosolized respiratory virus—do viruses only spread at night? What is “necessary” about having restaurant patrons masked while standing, and unmasked while sitting at their tables? What sense did it make to close down restaurants, yet keep bars open? And where were the CDC’s studies showing the benefits of masking, and providing substance for the invented rule of six feet of social distancing? One could go on about “measures” which were more often than not, mismeasures.

The other problem is a pointed one: am I saying that Legault (or you could insert Trudeau, Fauci, Walensky, etc.) is a Nazi? The argument is not a necessary one. Instead, what we learn from the linguistic comparison, particularly of policies enacted under the guide of “public health emergencies,” is that both the Nazis and other types of authoritarian regimes share a common lexicon and a similar syntax for articulating harsh policies. It is very rare for leaders and officials to drop their mask, as Emmanuel Macron did when he declared, “as for the non-vaccinated, I really want to piss them off”—that is no longer the “banality of evil,” it’s simply the petty vulgarity of evil. Otherwise, our cultural baggage is finite; the range of available ideas is limited, yet quite persistent; thus, it is not surprising to see such a degree of recycling.

Legault may not have been consciously drawing on Nazi discourse, and I am unable to summarize from where the Nazis drew their discourse about “public health”. I am interested in the use of neutralizing language to articulate extreme responses that rely on fomenting mass hatred and mass hysteria. If Legault, the Nazis, and other authoritarians who were a part of the global consensus have something in common—besides authoritarianism—it is either a shared fear, or a shared desire to instill fear.

Fear of what? Fear of “disease” spread by “dangerous Others”. When the Nazis depicted Jews as monstrous creatures bringing disease to innocent German towns, were the Jews not made to resemble Nosferatu, deliberately? (The German film, Nosferatu, features the villain sailing into town on a ship loaded with rats carrying the plague.) It seems that we are still reigned by primordial fears that were cultivated during the Medieval “Black Death,” along with its scapegoating, with the main innovation being the application of impersonal statist language when justifying rule by a state of emergency.

In Legault’s case, his favourite target was not just the non-vaccinated—it is any minority outside of the Quebecois mainstream. As soon as Covid was deemed to be “over,” without taking a moment to inhale Legault immediately jumped on the Anglophone minority, with an eye on eroding their school systems. Then he moved on to tackle immigrants and the decline of French usage. Then it was banning public prayers, which added to his government’s previous and ongoing outlawing of any public servants wearing religious symbols. (It is to the discredit of these various minority groups that they never recognized their common condition, and failing to make common cause they thus got picked off one by one.)

There always has to be a dangerous minority and an existential crisis—and in return, there must always be “special measures” to deal with them. Rule is seemingly becoming impossible without such “measures”.