From Hollywood to Hitler: Rethinking the Cultural Politics of Propaganda

Originally published on January 6, 2020

What is propaganda? What does cinema reveal about the Third Reich and its people? What are German films about during the Third Reich? What do they reveal? And what are they hiding? What does cinema know that we don’t? What is it that Germans dreamed about? What does German cinema tell that we have forgotten? How much of this cinema lives on in films after 1945, or in today’s films? Does German cinema still dream the old dreams, but in different form? What does cinema know, that we don’t?

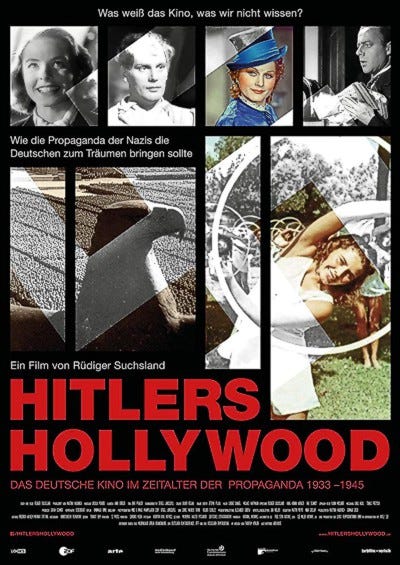

These are the questions that are posed in the documentary film, Hitler’s Hollywood: German Cinema in the Age of Propaganda, 1933–1945, a film by Rüdiger Suchsland, produced by Martina Haubrich, and narrated by the actor, Udo Kier. This is yet another major work produced by Europe’s Arte. The film runs for a total of 105 minutes—a heavy film, loaded with references to numerous German films, actors, directors, and dominated by a non-stop lecture under the guise of narration. This is a film that is primarily for scholars, and sometimes even about scholars, thus the film is partly dedicated to the memory of Karsten Witte, a prominent scholar of German cinema. The documentary does a fine job of showing the development of cinema in historical stages (though it abandons a chronological narrative); it follows the progress and decline of the Nazi regime during key events and critical years, thus amplifying the historical contextualization of the many movies that are featured.

This review will depart from past reviews published on Zero Anthropology; what is featured is more of a critical dialogue with the film, supported by key works produced by a range of experts on the history and politics of German cinema.

We can, however, first add some questions to the ones listed above. The first question should be: Was there a Nazi cinema? Such a silly question, one might easily conclude. However, from my self-directed, immersive crash course in this area of research, it does not appear to be a question that comes with an easy answer. German cinema in the Third Reich built on foundations previously laid, borrowed from foreign sources, and lived on in bits and pieces after the end of World War II. Having viewed some of the films featured in this documentary, I must confess that I was surprised and a little bewildered that these might be called “Nazi films”—they sometimes appeared to be subversively anti-authoritarian, even revolutionary, or other times as empty-headed and foolish as Hollywood musicals—but what seemed absent was any obvious Nazi presence or preaching. Others, however, are very clear examples of Nazi propaganda.

Other scholars, with the benefit of many years spent in this field of research, have raised further questions: “How can we use film, in research or in teaching, to engage historical questions? What sort of questions can be answered by such analysis, and what methods must be employed to answer them?” (Spector, 2001, p. 460). Also: “what better place than the cinema to find traces of the choices, emotions, and coping mechanisms of ordinary Germans?” (Petro, 1998, p. 42). Spector points to the problem of subjective interpretation and methodological shoddiness, while Petro provides an example of a problematic yet common assumption: that movies somehow represent the mentality of the intended audiences, that is, of ordinary people who had absolutely no role in the making of the movies.

What follows are three sections. The first is a straightforward though detailed summary of the film, presented without any critical commentary from myself. The second section delves into several areas of debate, with the aid of additional research. The third, the conclusion, offers an overall assessment of this documentary, and then presents the final score.

(1) Hitler’s Hollwood: A Summary

“Maybe we would understand more about the Third Reich, if we imagined that it was all a single film”—this is one of the concluding statements in Rüdiger Suchsland’s Hitler’s Hollywood (2017). One of the central tenets of this documentary is that we can understand Germany, and Germans, during the Third Reich by studying the movies produced in that period.

The film opens with this quotation from Siegfried Kracauer: “Watching old movies is a means of exploring one’s past”—the film frequently returns to Kracauer and particularly the analysis which he presented in his book, From Caligari to Hitler: A Psychological History of the German Film published in 1947 (available here).

The documentary works with a considerable archive of German films—all of the ones mentioned in the documentary are listed here in the order in which they were discussed:

Morgenrot (1933) by Gustav Ucicky

Stukas (1941) by Karl Ritter

Paracelsus (1942) by G.W. Pabst

Hitlerjunge Quex (1933) by Hans Steinhoff

Triump des Willens (1934) by Leni Riefenstahl

Eine Nacht im Mai (1938) by Georg Jacoby

Die kleine und die große Liebe (1938) by Josef von Báky

Frauen sind doch bessere Diplomaten (1941) by Georg Jacoby

Immer nur Du (1941) by Karl Anton

Der Schritt vom Wege (1938) by Gustaf Gründgrens

Durch die Wüste (1935) by J.A. Hübler-Kahla

Wasser für Canitoga (1939) by Herbert Selpin

Der Mann der Sherlock Holmes war (1937) by Karl Hartl

Die vier Gesellen (1938) by Carl Froelich

Zu neuen Ufern (1937) by Detlef Sierck

La Habanera (1937) by Detlef Sierck

Verwehte Spuren (1938) by Veit Harlan

Die goldene Stadt (1942) by Veit Harlan

Glückskinder (1936) by Paul Martin

Wir machen Musik (1942) by Helmut Käutner

Kapriolen (1937) by Gustaf Gründgens

Tanz auf dem Vulkan (1938) by Hans Steinhoff

Der Herrscher (1937) by Veit Harlan

Die Entlassung (1942) by Wolfgang Liebeneiner

Robert Koch, der Bekämpfer des Todes (1939) by Hans Steinhoff

Diesel (1942) by Gerhard Lamprecht

Ewiger Rembrandt (1942) by Hans Steinhoff

Friedrich Schiller—Der Triumph eines Genies (1940) by Herbert Maisch

Ich klage an (1941) by Wolfgang Liebeneiner

Auf Wiedersehn, Franziska! (1941) by Helmut Käutner

Der ewige Jude (1940) by Fritz Hippler

Robert und Bertram (1939) by Hans H. Zerlett

Die Rothschilds (1940) by Erich Waschneck

Jud Süss (1940) by Veit Harlan

Wunschkonzert (1940) by Eduard von Borsody

Das große Spiel (1941) by Robert A. Stemmle

Der große König (1942) by Veit Harlan

Ohm Krüger (1941) by Hans Steinhoff

Die große Liebe (1942) by Rolf Hansen

Zwei in einer großen Stadt (1942) by Volker von Collande

Großstadtmelodie (1942) by Wolfgang Liebeneiner

Der verzauberte Tag (1943) by Peter Pewas

Unter den Brücken (1944) by Helmut Käutner

Romanze in Moll (1943) by Helmut Käutner

Titanic (1943) by Herbert Selpin

Große Freiheit Nr. 7 (1944) by Helmut Käutner

Münchhausen (1943) by Josef von Báky

Die Frau meiner Träume (1944) by Georg Jacoby

Opfergang (1944) by Veit Harlan

Kolberg (1945) by Veit Harlan

(Materials for the documentary were sourced from 11 different archives. There are no interviews in the film—just clips from key films, accompanied by almost non-stop narration. A number of researchers have written that there is no one, central archive of all German films produced during the Nazi era, and furthermore, many films were destroyed after WWII; some have deteriorated with time in poor storage; and many are dispersed among several different collections, some of which are private. This is, therefore, a commanding collection of films for just one documentary presentation.)

The documentary opens by explaining that, in the 1930s, “most Germans had adjusted to the regime,” yet, “cinema offered an additional distraction”. The narration then jumps right to the point: “Nazi cinema was fantasy….it wanted to be a second Hollywood…Hitler’s Hollywood”.

German Cinema During the Third Reich

German cinema during the Third Reich was “filled with illusion, bigger than life, it wanted at all costs to be monumental, a spectacle, emotion, something for the heart and the eyes…but haunted by ambivalence”. Foreign actors were imported, and dominated the German cinema scene—even Ingrid Bergman got her start as an actress in German cinema during the Nazi period.

The makers of this documentary maintain that when it comes to Nazi-era films, “these films are better than their reputations,” and they “are worth a second look,” we should not look away. In addition, they alert us to the fact that, “some films disclose more than the makers intended”. “The best of them,” the narrator comments, “are self-reflective and reveal something beyond themselves”.

Nazi cinema was “show business”. When viewing all of the films listed above, it “all feels like it was part of one film”. “All of this is part of our collective memory,” the narrator states, adding: “all of this lives on in our subconscious”.

Cinema was central to the interests and concerns of Nazi leaders. Thus we are told that just three days after seizing power, Hitler went to see a film premiere about a WWI U-boat, Morgenrot (1933) by Gustav Ucicky, a film that “foreshadowed some of the themes of Nazi propaganda” such as self-sacrifice, “camarederie, soldier’s duty to the collective as a meaningful unit,” it was, “a film steeped in a mythical yearning for death”. Indeed this is a consistent theme in this documentary: that Nazi cinema was a form of necrophilia, that death was something to be longed for. The narration hammers this home: “the regime did not celebrate life but the cult of death….Nazi cinema seemed to be fascinated by death….every death was a happy death, often absurdly kitsch”.

Film, we are told, “was the Hitler regime’s primary means of communication with the masses”. Through film, we supposedly learn that Germans “clearly dream about ideals of a safe family life, of unspoiled nature, of a sound home”. Nazi cinema “created an artificially perfect world”. Thus, this documentary maintains that, “what is striking about Nazi cinema is a total lack of irony”—“instead there’s a rather forced cheerfulness”.

Joseph Goebbels was, “the highest-ranking PR man of the totalitarian state,” the patron of film—Goebbels controlled scripts and casting. The documentary quotes Goebbels himself:

“Propaganda is an art form. Propaganda has just one objective, and that objective is to conquer the masses. Alluring people into an idea so in the end they are captivated by it, and can no longer free themselves from it”.

Not all German actors and directors were allured of course. Marlene Dietrich, already working in Hollywood, stayed out of Nazi Germany. Fritz Lang, who made Metropolis, also left Germany. George Pabst however got stuck in France just as it was occupied by Germany, and he was forced to work in Nazi Germany, but then performed a balancing act with his films, such as Paracelsus (1942)—here is a clip from the film as presented in this documentary, and it is both haunting and beautiful:

Many films thus escaped the totality of totalitarianism—which is another of this documentary’s key themes.

The documentary tries to follow the Critical Theory of the Frankfurt School, particularly the work of Siegfried Kracauer. The filmmaker thus adopts Kracauer’s definition of propaganda:

“Propaganda is totalitarian, regressive and nihilistic. You remove any remaining substance from meaningful terms, and use their shell to advertise with an enticing appearance. From beneath the tumult of propaganda a skull appears”.

The argument advanced in the documentary is that “cinema is the seismograph of its time, an indicator of the cultural subconscious of an era”. In addition, “cinema knows something that we don’t know”. To discover what cinema knows, we have to decode it, since “it has an underlying meaning that can be exposed”.

The documentary then moves into relatively condensed, short, and fast treatments of individual films, not following an obvious structure of an argument, nor does it always follow film development according to a strict chronology (just as the list of films above shows). About Hitlerjunge Quex (1933) by Hans Steinhoff, the documentary calls this the Nazi’s “first effective propaganda film”; multiple scenes from the film are shown, culminating in the transcendent death of Quex, a young boy who joined the Hitler Youth and was murdered by Communists. No information is provided about audience reactions or the number of people who went to cinemas to see the film. Interestingly, Triumph of the Will, or Triump des Willens (1934) by Leni Riefenstahl, does not occupy a central point of attention in this documentary, even if it is probably the only propaganda film which non-specialists with a general knowledge about Nazi Germany will be able to name. About Riefenstahl’s film, the narration talks about how “the politics of aesthetics were followed by the aesthetics of politics,” and that the design of the film was about “dissolving the individual into geometric conformity”. The documentary then quotes Susan Sontag: “history became theatre….the image is no longer simply the record of reality; reality has been constructed to serve the image”.

Well into the documentary we are informed that over 1,000 films were produced during the Third Reich; over 500 were comedies and musicals; around 300 melodramas, adventure, and detective films; and, period dramas. There were many films in which women were the protagonists, since women made up the bulk of the home audience. Movies also featured tales of the exotic set in distant lands.

We are then told that the filmmaking company, Ufa, founded in 1917, helped Hitler’s rise to power; in 1937, the state took over Ufa, and then other film companies were shut down. By 1942 there was just one state-run monopoly responsible for making films. The narration adds: “Nazi cinema was built upon illusion; here cinema really became a dream factory”. Actors in the Third Reich had some of the best-paying jobs; many of them were foreign. As for Ingrid Bergman, all she would ever say about her experience in Nazi Germany was that “she declined to have tea with Goebbels”. German cinema resembled Hollywood in the centrality of “stars” in public culture. Cinema was such a valued part of that culture, that the documentary states: “cinema was part of the total art work of the state”.

Speaking of tales of the exotic, the documentary turns to Durch die Wüste (1935) by J.A. Hübler-Kahla, and says that it was “like a German Lawrence of Arabia”. The narration continues by calling such films, “opium for distracted people”. The documentary argues that in German films in this period, the dominant aesthetic was to show “everything…in uniformity and lockstep”. “Period dramas were popular,” featuring “great Germans in uniform”.

Feminist Nazi Film?

Melodramas were also popular, focusing on love conflicts; generally “about minor gender trouble,” the main protagonists of these movies were usually women. The documentary veers, at different times (themes are fragmented in the presentation), into a discussion of a kind of “feminism” that took shape in German cinema of the Third Reich. Speaking of Die vier Gesellen (1938) by Carl Froelich, we are told that it is a movie about four women who are friends and want to set up a graphic design business of their own after completing their studies. However, conservative values prevail in the film, as the women fail, succeed, then fail again and decide to choose marriage instead—“but for a long, shining moment, women’s liberation seemed possible” in the film, that narration maintains. In the case of Wir machen Musik (1942) by Helmut Käutner, the documentary comments on its contents: “there are hen-picked men and very assured women who are equals in the gender war”. Auf Wiedersehn, Franziska! (1941) by Helmut Käutner is presented in the documentary as an example of how cinema during the war was increasingly aimed at female audiences; it dealt with “women’s fantasies”. Großstadtmelodie (1942) by Wolfgang Liebeneiner was, the documentary argues, the best example of a “feminist” film in Nazi Germany. In it a countrywoman becomes a professional photographer: “the film shows that women gaze at things differently”. Here we see “a woman who doesn’t pursue men, who doesn’t want a family or children, who is friends with a man without being in a love relationship”. It is a film that places value on privacy, self-determination, that shows workers’ daily lives. Barely a uniform is seen in the film, that is until the very end when Goebbels himself appears speaking on stage at a rally.

Departing radically from any pseudo-feminist ideals, one of the key actresses of the era (I repeatedly missed the name—she is featured in the photo) is held out by the documentary as “the perfect embodiment of Nazi perversion”: a Nordic blonde actress who prominently displayed devotion and “tearful innocence,” and always died on the screen. She supposedly came to be known as “the floating corpse,” which the documentary maintains is evidence of “the necrophilic core of Nazi male fantasies”.

Rogue Elements?

Aside from quasi- or proto-feminist themes, there were other “rogue” elements of so-called “Nazi cinema” (or more accurately, cinema of the Third Reich) that defy what we might expect of a regime of totalitarian propaganda. Thus Verwehte Spuren (1938) by Veit Harlan makes prominent panic, repressive and secretive “reason of state,” and press censorship. These are all themes that played out in this movie, “a film of uncertainty in the otherwise overly certain German productions”. Also roguish, there was Kapriolen (1937) by Gustaf Gründgens.

Gustaf Gründgens, who was adored by Göring and loathed by Goebbels, was “a Janus-headed artist” who worked somewhere between “collaboration and resistance”; he “overstepped boundaries in both directions,” the narration explains. However, Tanz auf dem Vulkan (1938) by Hans Steinhoff was a film that Goebbels permitted, starring Gründgens in a one-man show where he speaks of “bombs” hidden in secret conversations, and the desire for “rebellion” played out among scenes of open revolution. The film shows an artist challenging the authorities, even if the material is displaced into the imaginary setting of the French revolution. Unter den Brücken (1944) by Helmut Käutner was banned: “too intimate, too civilian, and too human,” the narrator comments; the movie showed a love triangle between one woman and two male friends. It also depicted lives and scenes totally detached from and untouched by war. The narrator explains that Helmut Käutner was an “anti-fascist in his soul and in his attitude”. Romanze in Moll (1943) by Helmut Käutner shows how Käutner “cleverly found thematic niches in the Third Reich, to make almost independent films under the regime”—this film was also about a love triangle.

A rogue among the rogues was Titanic (1943) by Herbert Selpin—it should have received applause from officials. Nazis were after all fascinated with the Titanic story: for them it was a story about how “evil capitalists and the Jews were to blame” for the sinking of the Titanic. Interestingly, “the film celebrated the glamour of the empire, even as it pretends to despise it”. The film “does not celebrate technology or progress, which are a part of fascism,” the narrator adds. Most of the women in the movie “are shown in a positive light. This film was made for women. The women…realize that men’s hunger for power will result in the downfall of the ship or the state. Titanic was an allegory for what was happening in Germany”. However, “after the events of Stalingrad, this was too much for Goebbels. Titanic was banned in Germany; only in occupied countries could it be seen”.

The Audience

The documentary adopts the “hypodermic needle model” of media analysis. Turning to Zu neuen Ufern (1937) by Detlef Sierck (who later became Douglas Sirk when he moved to Hollywood), the narrator argues that such films were, “imitations of life, that worked like drugs, slowly seeping into the audience’s subconscious and dispensed their sweet magic”. The documentary thus makes certain assumptions about audiences, as evidenced by the prominent place it gives to this quotation from Hannah Arendt:

“The effectiveness of propaganda demonstrates one of the chief characteristics of modern masses. They don’t believe in anything visible, not in the reality of their own experiences. They do not trust their eyes and ears, but only their imaginations. What convinces masses are not facts, not even invented facts, but only the consistency of the illusion”.

Hollywood

As for Detlef Sierck/Douglas Sirk, the documentary notes that some of the prominent emigres from Nazi cinema, who “had a smooth ride for years,” later went on to become successful in Hollywood. La Habanera (1937) by Detlef Sierck is one of the films discussed briefly in this documentary, which is another example of German cinema’s fascination with the exotic (only to highlight the virtues of Northern, Germanic living). Despite the title, the film was set in Puerto Rico, and featured a German emigré making a home in the island, ruled by a corrupt despot, until an epidemic sweeps the island and she decides to return home.

Hollywood exercises an important presence in this documentary. Here we are presented with Glückskinder (1936) by Paul Martin. Glückskinder (see the clip below) was Goebbels’ remake of It Happened One Night, which is the high point of German Nazi imitation of Hollywood—“a screwball comedy with slapstick and sparkling dialogue”. Why were Hollywood productions the template for popular German films during the Third Reich? One reason has to do with widespread German preferences, which were reflected even by Nazi leaders, who apparently had little trouble in creating exceptions to their own nationalist preferences: “in private, Hitler watched Mickey Mouse cartoons, Frank Capra films, musicals…this led to a series of attempts to Americanize German cinema and to copy Hollywood”. As for Goebbels, Britannica has this to say:

“Many of his cultural policies were fairly liberal….Even his propaganda messages were limited by the rationale that ceaseless agitation only dulls the receptive powers of the listener. As far as Goebbels was concerned, efficiency took precedence over dogmatism, expediency over principles” (emphases added).

Thus there was an important degree of openness to the American model at the top tier of the Third Reich.

Nazi War Cinema

With the outbreak of WWII, German cinema emphasized both war propaganda and light entertainment. As the documentary explains, “there were some films which legitimized some overstepping of limits,” by preaching genocide, torture, and euthanasia of the vulnerable. Some of the films showcased in this portion of the documentary are nothing short of ghastly, and thus come much closer to what most would expect of cinema during the Third Reich, that is, of a clearly Nazi cinema. Thus Der Herrscher (1937) by Veit Harlan, even as an ostensibly anti-capitalist film, instead directs its ire only against specific prominent families who dominated industrial capital. In Ich klage an (1941) by Wolfgang Liebeneiner euthanasia is practised against the mentally ill (including children), glamorized by Liebeneiner in the form of a “happy death”. Newsreel shown in cinemas showed dancing African soldiers, from French colonies, and mocked them as barbarians whom the Allies hold up as “the custodians of [Western civilized] culture”. In a similar vein, though connecting with anti-Semitism, Der ewige Jude (1940) by Fritz Hippler manifests the fact that “there’s a straight line from racism to anti-Semitism,” and the documentary shows the outgrowth of anti-Jewish discrimination emerging from a bedrock of anti-black racism, or at least showing the two as parallel phenomena. Anti-Semitic incitement was prominent in Robert und Bertram (1939) by Hans H. Zerlett and Die Rothschilds (1940) by Erich Waschneck. The documentary states that “an ugly secret understanding existed between Nazi anti-Semitism and the rest of the Germans, who knew and wanted to suppress it”. Most notorious was Jud Süss (1940) by Veit Harlan—here cinema clearly prepared the way for the Final Solution. The film was shown in 15 European cities and to all SS teams. The central character, a cosmopolitan Jew, works his way into aristocratic circles, rapes a woman, and is then sentenced to death after all his wrong-doings are exposed. The star, Ferdinand Marian, was a raging hit with audiences.

Robert Koch, der Bekämpfer des Todes (1939) by Hans Steinhoff was typical of period dramas that were prominent in German cinema during the Third Reich in wartime, featuring elaborate costumes, commemorating events of the past, and memorializing “Great men” of German history. This was done, the documentary argues, in order to distract audiences seeking relief from the present; rather than remembering history, this was “a strategy of forgetting,” all far-removed from historical reality.

Also during WWII, Ohm Krüger (1941) by Hans Steinhoff critically depicted concentration camps (see below)—only they were the camps established by the British to confine the Boers in South Africa during the Boer War. Die große Liebe (1942) by Rolf Hansen was “a morale-boosting film,” that transformed “an air raid into a romantic event…love strikes like a bomb attack” as the narration mocks the mix of love and war.

A rousing example of morale-boosting is shown in the clip here:

The Apocalypse

The documentary also features a series of films that seem to evoke an apocalyptic sense of Nazi doom, of impending annihilation. Thus we are told that Große Freiheit Nr. 7 (1944) by Helmut Käutner, “in splendid colour,” is a movie that “contradicts Nazi values”. One of the stirring songs features the line, “it will be over some day”. Once again the movie presents a love triangle. Men are shown as “sentimental, fully broken”.

Movies of the final years sometimes displayed an “exaggerated cheerfulness” that masked a deep unhappiness. Münchhausen (1943) by Josef von Báky is characterized by the documentary as a case where “propaganda was becoming a farce” and where entertainment took an apocalyptic turn.

Die Frau meiner Träume (1944) by Georg Jacoby is described as being “like a film on acid”. The narrator adds: “the longing for a better world, in 1944, must have been tremendous”. “There is something hysterical about” this movie, the narrator says, adding that it is, “a film for the final days, a refection of the German state of mind”.

Opfergang (1944) by Veit Harlan shows a Germany that “is a place of illusions,” as everyone appears in a mask. In addition the movie “shows the decadence of the bourgeois world, the old and faded upper class as it comes closer to collapse”. The documentary spotlights Harlan’s work as emblematic of the Nazis’ collapse: “Harlan’s films predicted that the end was near. His last two films are rehearsals for the downfall”.

Most spectacular, almost as a dress rehearsal whose script predicted the storming of Germany by foreign invaders, Kolberg (1945) by Veit Harlan was the most expensive film ever made in Germany. It deserves to be known as much as, if not more than Triumph of the Will. The movie involved an enormous expenditure of resources when the Nazis had few to spare: it was made with 6,000 horses and 10,000 costumes, and over 100,000 extras. In fact, “the movie cost eight and a half million Reichsmark (eight times more than the normal German film), involved 187,000 individuals including entire army units, and comprised ninety hours of unedited footage. Though there was a shortage of ammunition on the eastern front factories worked overtime to produce blank bullets for the movie” (Weinberg, 1984, p. 113). The movie is a historical drama about Prussia being vanquished by Napoleonic forces, and how Germans stood up in a desperate, last-ditch effort of defence—“now that it was inevitable, the downfall became heroic”.

After the destruction of the Nazi state, several of the key filmmakers and prominent actors and actresses of the Third Reich continued working in cinema in West Germany after the end of WWII. Some died as recently as 2005. They made dozens of new films in post-war Germany. Indeed, while in 1980, “Nazi films comprised 8.7 per cent of all features aired on West German stations, a total of 113 titles,” by 1989, “the number had risen to 169” (Rentschler, 1996, p. 316).

(2) Cinema of the Third Reich: Problems, Questions, Surprises

(a) Was there a “Nazi Cinema”?

“Even the phrase ‘Nazi cinema’ deserves caution,” wrote Eric Rentschler, a specialist on cinema during the period. He then asked: “do all German films made during the Third Reich indeed warrant this appellation?” (1990, p. 257). Nazis did not sweep into power and immediately take full control of the film industry; it was a gradual, incremental, even halting process that only came into full fruition late in the regime’s existence, at the height of total war (Weinberg, 1984, p. 114).

Another reason for doubting the validity of “Nazi cinema” as a categorization, is that the cinematic productions manifested a degree of continuity with previous periods, and built on already existing foundations. “Gloom, fatalism, and disorientation” dominated the cinema of the Weimar Republic, which some analysts saw as a psychological manifestation of a desire or “predisposition for authoritarianism and control”; this was also a time in which government and heavy industry had invested significantly in the organization of the German film industry, thus even before the advent of the Nazis (Petro, 1983, p. 48).

Josef Goebbels seemed to make cinema the centrepiece of the Nazis’ cultural politics:

“We are convinced that in general film is one of the most modern and farreaching methods of influencing the masses. A regime thus must not allow film to go its own way” (quoted in Weinberg, 1984, p. 105)

Such pronouncements would lead film historians like Eric Rentschler to remark that “‘Hitler’s regime can be seen as a sustained cinematic event,’ even that ‘the Third Reich was movie made’”. Other historians judged this to be hyperbolic, overly metaphorical, or a partial truth (Spector, 2001, p. 462).

Yet it was the interplay of four major factors that would decide whether the Nazis would have their way with cinema, and to what degree: 1) the “personality of the leadership and of Josef Goebbels in particular”; 2) “the internal dynamics of bureaucracy”; 3) “the changing economic needs of film companies in the 1930s and early 1940s”; and, 4) “the perceived role of film in the dissemination of nazi propaganda” (Weinberg, 1984, p. 107). None of these was predominant over the years, and they frequently contradicted or complemented each other—for example, in 1933, the film industry’s reliance on the crucial support of movie-going audiences blocked attempts by ideologues to nationalize the film industry at that time.

What is curious is what is revealed by some of the statistics of cinema during the Third Reich—bearing in mind, however, that “scholars disagree over the exact number of feature films produced under the Third Reich, but the figure is somewhere between 1150 and 1350” (Weinberg, 1984, p. 111). According to Rentschler, “of 1,094 feature films, 523 were comedies and musicals; 295 were melodramas and biographical pictures; 123 were detective films and adventure epics; only about 14% of films were manifestly propagandistic, like Hitlerjunge Quex” (1990, p. 259). Others apparently concur, even if their conclusions are even stronger: “Hollywood-style light features or ‘heitere Filme’ (musicals, comedies, and romances)…made up as much as 90 percent of the German film industry’s production between 1933 and 1945” (Spector, 2001, p. 468). Rentschler had a similar figure, noting: “the vast majority of films made under Goebbels in fact bear few overt signs of ideological resolve or official intervention. So-called ‘unpolitical’ features constituted 86 percent of the epoch’s films”; moreover, besides a mass of melodramas, crime stories, and biographical pictures, “almost half of all features were comedies and musicals” (1994, p. 37).

What do we make of all the lighthearted comedies and musicals of the period, so many of them following an American model? Here we are reminded of an important lesson: “National Socialism could not—and did not—rule by terror alone”—instead “emotional engineering” that “proffered tourism, consumerism and recreation as dialectical complements to law, order and restriction” required that such movies be made (Rentschler, 1996, p. 317). As some have noted, “Fascism had a sinister visage, but it also had a pleasing countenance,” thus, “very few Nazi features simply rant and rave; most of them appear to have nothing to do with politics” (Rentschler, 1996, p. 317). As Rentschler explained:

“We cannot reduce all Nazi films to hate pamphlets, party hagiography or mindless escapism. This cinema, in fact, is neither singular nor aberrant; its conscious reliance on classical Hollywood conventions has gone virtually unnoticed as has the recourse of so many productions and so much of Nazi mass culture to American techniques and popular genres. Much of its fatal appeal derived from a modern populace’s desires for a better life”. (1996, p. 317)

New books published in the late 1990s argued that “the traditional, bifurcated view of German cinema between 1933 and 1945 as either a tightly controlled vehicle for state propaganda or else an escapist diversion from a hyperpoliticized everyday must be discarded” (Spector, 2001, p. 462). However, even “films with the most blatant propaganda messages,” were “fraught with contradictions and resistances” that were fundamental to their structures (Spector, 2001, p. 462). One argument then is that “propaganda” vs. “entertainment” is a false dichotomy: propaganda is very malleable, and entertainment is too complex to be reduced (Spector, 2001, p. 462).

Thus one approach to the propaganda vs. entertainment question is Rentschler’s, which sees films as part of a bargain: a consumer good, a reward for sacrifice, remuneration designed to placate and anaesthetize (1994, p. 37).

Another approach is Spector’s, which sees the emphasis on entertainment as itself bearing an imprint of official Nazi interests: “Historians and film scholars alike are aware of the special place the Nazi propaganda ministry reserved for the film industry, and that this interest was primarily focused on entertainment rather than propaganda film. Joseph Goebbels’s and Adolf Hitler’s personal interest in entertainment film is well documented” (Spector, 2001, p. 461).

Yet some authors are comfortable with tilting toward one side of the dichotomy over the other. For example, some studies have presented the case that the push for propaganda films under the Nazis was hamstrung. David S. Hull whose book, Film in the Third Reich, was perhaps the most popular of all works on Nazi cinema (according to Weinberg, 1984), argued that “the government had little success in its attempt to impose its ideas upon German filmmakers and their productions”. The “ridiculous obsessions of a few nazi ideologues” generally “gave way to the realities of film-making—the need to make profits and the unwillingness of German audiences to sit through propaganda fare; the dogged independence of the members of the film community; and the prohibitive cost of producing large-scale epics” (Weinberg, 1984, pp. 111–112). Hull insisted that no more than 25% of German movies produced annually could be defined as propaganda (Weinberg, 1984, p. 112). Further bolstering the argument against propaganda we learn that, “audiences were so hostile, especially after 1941, that it was common practice to lock the doors of theatres during the showing of such films” (Weinberg, 1984, p. 112).

Pushing toward the other side of the dichotomy, according to Weinberg (1984) Erwin Leiser argued in his work, Nazi Cinema, that “practically all films produced under the Third Reich contained some element of propaganda”. He rejected any differentiation between “political” and “entertainment movies”. Though he admitted that Goebbels himself was “averse to heavy-handed ‘message’ films, Leiser insists that even escapist films contained nazi ideals or at least served to lull German audiences into forgetfulness” (Weinberg, 1984, p. 112).

The documentary under review gave ample room to the work of Siegfried Kracauer and his book, From Caligari to Hitler. However, the book actually had very little to say about National Socialist feature films themselves (Rentschler, 1996, p. 316). One of the flaws of his work, according to scholars specializing in the field, is that Kracauer assumed a direct equation existed between the political structure of the Nazi regime and cinematic productions (Petro, 1983, p. 48), that is, that there was an authentically “Nazi cinema”.

By relying so heavily on Kracauer’s work, this documentary, like the earlier “propaganda camp” that dominated studies of cinema in the Nazi period, assumes that ideology is monolithic, all-encompassing, top-down, and without meaningful escape (Spector, 2001, p. 464). Indeed, throughout the scholarship of cinema during the Nazi period, there seem to be lots of excuses made for theorizing in the absence of direct empirical research with actual audiences, added to the prevailing assumption that cinema is a kind of touchstone for revealing the inner nature of a society (Petro, 1983, pp. 48–49). This assumption is based on a number of common analytical flaws, one being a basic one: the slip from society to culture, the idea that social facts reveal themselves as cultural phenomena. Thus we are distanced from social facts, and forced to view them through a distorting cultural lens. Kracauer in particular assumed a “simplistic and unmediated correspondence between social and cultural phenomena” (Petro, 1983, p. 51). One can understand why some scholars have criticized Kracauer for his “weak methodology” and his use of “ambiguous terminology” (Weinberg, 1984, pp. 117–118).

Paul Monaco also treated films as the dream images of the nation (Petro, 1983, p. 55). He assumed the existence of a “mass national audience” and he assumed that filmmakers were expert interpreters and analysts who could perceive and give expression to this collective (un)conscious(ness). Thus filmmakers were rendered transcendent, as if they were chroniclers of the nation’s cultural history. But then such an approach cannot explain evidence contrary to the thesis: American films with huge popularity in Germany, and German films that became major box office successes in the US (Petro, 1983, p. 57). This would mean that distant Americans were somehow first-class interpreters of “the German soul,” and likewise Germans were premier decoders of American cultural values.

One leading anthropologist comes in for particular criticism—Gregory Bateson, revered by many North American anthropologists, and viewed otherwise outside the discipline:

“A far less successful effort to apply social scientific methodology to the study of nazi propaganda film content is Gregory Bateson’s analysis of Hitlerjunge Quex found in Margaret Mead and Rhoda Metraux’s The Study of Culture at a Distance (Chicago 1953, 302-14). Using techniques borrowed from cultural anthropology, Bateson treats the film as a myth, embodying the collective self-image of Germans living under nazism. The article is filled with impressionistic musings and pseudo-Freudian commentary on life in the Third Reich. Like Kracauer’s study of Weimar films, it ignores the nature of film production and its effect upon film composition and assumes a German ‘collective mentality’, which allegedly underlies the perspective of both the nazi propagandist and the average German movie-goer”. (Weinberg, 1984, p. 118)

(b) Hollywood Inspired the Nazis

If there are elements that make a film a fascist film, then Hollywood films would be no less fascist. There are numerous instances of German films during the Third Reich, and film stars, modelling themselves on their Hollywood counterparts, often in direct correspondence as a nearly perfect mirror, as detailed by Witte (1998). “In the endeavor to create the definitive dominant cinema,” Rentschler wrote, “Goebbels and his minions in crucial regards let Hollywood be their guide” (1994, p. 38). It was in American cinema that the reviewers of the Propaganda Ministry realized the shape and content of the popular German films they wished to make (Rentschler, 1994, p. 38). “The utopian energies tapped by the feature films of the Third Reich,” Rentschler later observed, “in a crucial manner resembled, indeed consciously emulated, American dreams” (1996, pp. 317–318). Others concur, observing as well the Nazis’ “infatuation with Hollywood” (Von Moltke, 2007, p. 70).

“I present the Führer with thirty of the best films from the last four years and eighteen Mickey Mouse films for Christmas. He is very pleased”. (Goebbels, from his diary for December 20, 1937, as quoted in Rentschler, 1994, p. 38)

“We cannot reduce all Nazi films to hate pamphlets, party hagiography or mindless escapism,” Rentschler argued. German cinema of the Third Reich was marked by “its conscious reliance on classical Hollywood conventions,” a fact that “has gone virtually unnoticed as has the recourse of so many productions and so much of Nazi mass culture to American techniques and popular genres” (1996, p. 317). Germans identified with American consumerism, as the basis for their ideals of a better life.

If the point of this documentary was to prove that cinema during the Third Reich reflected totalitarian propaganda, then it ended up doing the same with respect to Hollywood (only without actually saying so). And if Hollywood projects totalitarian propaganda, then according to the logic of this documentary, cinema reflects the overall society and regime in which it is produced.

As Rentschler argued, the German dream factory of the thirties and forties appropriated and consciously recycled Hollywood fantasies (1990, p. 260). He remarked that, “one could imagine quite productive comparative analyses…between It Happened One Night and Glückskinder, The Quiet Man and Der verlorene Sohn, Young Mr. Lincoln and Friedrich Schiller, The Story of Louis Pasteur and Robert Koch, Bataan and Kolberg (Rentschler, 1990, p. 261). Moreover, “fan weeklies and women’s magazines closely followed the activities of Hollywood stars”; and, programs of Disney cartoons remained widely popular at Christmas each year (Rentschler, 1994, p. 38).

Scholars of German cinema during the Third Reich observed a phenomenon which most of us are either unaware or ignore—Americanization:

“Was there a perceived contradiction between official invocations of National Socialist cultural purity and the undeniable presence of American products?…Germany in the Thirties was the site of an unabashed Americanism that shaped consumer habits and affected daily behavior every bit as strongly as Party doctrine. For instance, in 1939 Coca-Cola had more than 2,000 German distributors as well as 50 bottlers. Ocean liners bound to New York departed every Thursday from Hamburg. Modern appliances well known from American movies and magazines—electric coffee makers, stoves, refrigerators, washing machines—increasingly found their way into German households. Until war broke out, one could purchase a wide array of international periodicals on most big-city newsstands. Numerous books about the United States with a pro-American slant appeared between 1933 and 1939. German movie weeklies….regularly featured Hollywood stars on their covers, while fashion journals conveyed makeup tips and ads for the latest American cosmetics and lingerie. Despite official proscription, jazz flourished. American mass culture, its consumer items and pop icons, continued to teach Germans what it meant to live in a modern world”. (Rentschler, 1994, pp. 39–40)

Even the Nazis’ own program of cultural imperialism was a mimetic one, rooted in imitation of the US. Goebbels wrote in his diary on May 19, 1942: “We must take a similar course in our film policy as pursued by the Americans on the North American and South American continents” (quoted in Rentschler, 1996, p. 319). The Nazis’ dreams of conquering world cinema were simply a translation of similar American dreams.

One can look at the Hollywood–Third Reich nexus in another way, beyond film aesthetics and plots, and instead look at actual institutional collaboration and complicity. The intricate and intimate interrelationships between German cinema of the Nazi period and Hollywood was the subject of Ben Urwand’s 2013 book, The Collaboration: Hollywood’s Pact with Hitler. Urwand found that, to put it simply, Hollywood willingly assisted the Nazis. Once Hitler came to power in 1933, “the major Hollywood studios tacitly agreed not to portray Germany in an unfavourable light or to mention its persecution of the Jews” (Quinn, 2013). What resulted was, “a shameful policy of compromise and kowtowing on the part of the studio bosses,” and what made the situation even more ironic was the fact that, “those bosses who did their utmost to appease the crazed ideology of Nazism were by and large Jews themselves” (Quinn, 2013). The Nazis tightened their editorial stranglehold in Hollywood even further after 1933, “by the appointment of their very own watchdog in Los Angeles” (Quinn, 2013). The Nazis were on the alert for any possible negative depictions of themselves in the world’s most popular cinema; Hollywood, for its part, was afraid of jeopardizing its business interests in Germany (Quinn, 2013). One scholar lists the reasons for Hollywood’s complicity as follows:

“American disbelief, apathy, and even acquiescence toward subsequent Nazi purges of the film industry; studio preoccupation with foreign markets and a concurrent vanishing of identifiably Jewish characters from the screen; and abortive attempts to make anti-Nazi films outside the mainline studio system and the purview of its self-censorship apparatus, the Production Code Administration”. (Carr, 2015, p. 244)

As Carr noted: “one was more likely to find studios tolerating anti-Nazi politics so long as such civic engagement remained well-insulated from the filmmaking process” (2015, p. 245). Even within the US, there were political interests that indirectly safeguarded Nazi interests: the anti-New Deal Democrat, Martin Dies Jr., was hostile to any form of “radical politics,” and was suspicious of both Jews and Hollywood. Far from worried about the Nazis, it was this combination of fear of radicalism, Jews, and Hollywood that led many disgruntled American citizens to perceive them as “a single threat, one that was a far greater danger to democracy” (Carr, 2015, p. 245). Anti-Nazi films were thus more likely to be seen as dangerous propaganda, than those that were neutral or indifferent.

All told, there were “multiple divisions, displacements, borrowings, and doublings” that delineate the “‘special path’ between Hitler and Hollywood” (Von Moltke, 2007, p. 70). Witte asked: “Did Ufa and Cinecittá have more in common with the Hollywood studio system than they might have wished to acknowledge?” (1998, p. 23)—but we could turn the question around. Indeed Witte also found that, “German cinema of the Third Reich had little to call its own. It was a borrower” (1998, p. 29).

We thus need to stop asserting that “propaganda” was somehow invented by German Nazis, when its own propaganda was essentially derivative of American forms and models, copied from Hollywood itself.

(c) Assuming Audiences

When it comes to German audiences during the Third Reich, there are more assumptions than answers, and more answers than questions. In this documentary, like in much of the scholarship—and much of media studies generally—the mind of the audience is read from the films they watched, as if they saw exactly what was intended for them to see. They are thus cast as dry sponges, ready to be filled with the water of cinema. Their heads are empty vessels, into which cinema injects its coded meanings using a large hypodermic needle.

The fact of the matter is that, under the Nazis, who so valued film (we are told)—the actual number of cinematic productions fell when compared to the last years of the Weimar Republic: “Between 1928 and 1933 Germany led Europe (excluding the Soviet Union) in the number of films produced: the average German output per year was 180, as compared with 125 for Britain, Germany’s nearest European competitor”—but this dropped to less than 100 under Goebbels (Padover, 1939, p. 142).

On average, German films lost money during the Third Reich (Padover, 1939, p. 143). German weekly cinema attendance was anemic, and only a fraction of what it was in France, Britain, the US, and Australia (Padover, 1939, p. 144).

Overt propaganda films did especially poorly. We see this in the “marked lack of success” for films like Quex, as audiences largely chose to stay away (Padover, 1939, p. 145). We learn that “the German public…tired of looking constantly” at a world shown by Nazi cinema in stark black and white terms—instead the public flocked to the few foreign films that the censors allowed to be shown in Germany (Padover, 1939, p. 146).

Even when it came to Jud Süss, which was instead immensely popular, the authorities intervened to contain it, ironically: “the film was banned to viewers under fourteen after teenagers emerging from the theatre beat up Jewish passers-by” (Weinberg, 1984, p. 116). “Audiences were quite selective in their preferences,” cheering some propaganda films, yet booing scenes in others; packing cinemas for comedies and musicals, yet largely staying away from overt propaganda features (Weinberg, 1984, p. 123). Propaganda was not necessarily a matter of authoritarian imposition from above.

(d) Rogue Elements

“Not all of the films produced in Nazi Germany were automatically Nazi films,” Witte cautioned, adding: “but neither was every film banned in those days an instance of aesthetic resistance” (1998, p. 29). We often assume that Nazi censorship would have been rigorous, strict, loud and commanding, with orders barked by officials at directors. The reality was far more subtle and complex:

“The censorship is particularly subtle because it is vague and negative. No director or producer is told what to do or not to do; there are no specific regulations governing the industry. But a perpetual hammer of suppression hangs by a thread over every studio. The authorities allow freedom of production, only to crack down the more effectively upon the completed work. The insecurity thus engendered works greater havoc than positive interference”. (Padover, 1939, p. 144)

If censorship in any form was needed, it was precisely because German cinema was not wholly on the same page as Nazi ideologues—which takes us back to the question of whether there was a “Nazi cinema”. The films produced during the period can be read as texts: “these texts might contain potential meanings beyond their official calling” (Rentschler, 1990, p. 259).

What we learn—and the documentary itself helps to bring this to light—“collusion and resistance can coexist” and “certain forms of resistance are built into or are produced by the repressive ideology itself” (Spector, 2001, p. 466).

(3) Hitler’s Hollywood: Concluding Thoughts

If the documentary provoked a review/analysis of this length, it can almost certainly be seen as a positive reflection of the productive nature of the documentary. That does not mean that the documentary’s narrative is free of flaws—far from it. Some of the flaws are some that have been widely acknowledged as significant flaws in media analysis, for decades now, such that their reappearance in this documentary is inexcusable.

For example, one of these flaws is that the documentary speaks for the masses: the documentary filmmaker assumes the voice of the elite critic, who then assumes that his analysis is an echo of the voice of the masses. The analyst thus substitutes for the people. Ironically—strangely—the documentary thus aligns itself with the same political positionality which it critiques: elite dominance of the many, one that silences the voices of the many. In critiquing totalitarianism, a totalitarian methodology is adopted and reinforced.

In a related vein, the documentary assumes that cinema is like some sort of social super-brain, one that stands for the consciousness of an entire society, that reflects its memory. This is captured in the notion that cinema is a way for all of us to explore our past. For that to hold true, then filmmakers would have to be fully in tune with the depth and breadth of society; they would need to possess a maximum consciousness and ability to perceive, understand, and thus manipulate key symbols. Furthermore, what they produced was what was demanded. This assumes that movies document social history, one’s own history, that cinema stands in for memory; it assumes that movies accurately reflect the spirit of an age, rather than the biases, preoccupations, and ideologies of a film-making elite.

Also related as a flaw is the documentary’s extreme reification if not festishization of film, investing film with almost super-human power. We are told that cinema has human attributes such as “knowing,” and that cinema may be able to “know” more than any of us. But if there is any knowing to be done, it can only be done by us—cinema as such can know absolutely nothing.

The documentary opens by implying that propaganda was limited to a specific “age,” a phase in history. This suggests that we are now living in a post-propaganda world, a contention that is impossible to accept. The documentary also states that “Nazi cinema was fantasy”—but that sounds like all cinema. The documentary speaks of Nazi values in films, such as scenes depicting self-sacrifice, camarederie, and a “soldier’s duty to the collective as a meaningful unit”—which sounds an awful lot like a lot of awful American war films today. Further, the documentary asserts that “Nazi cinema created an artificially perfect world”—but this sounds exactly like most Hollywood movies; “what is striking about Nazi cinema is a total lack of irony”—again, perfectly Hollywood. The documentary speaks of German films as encoding synchronization, order, conformity, everyone brought into line in lockstep—but we can see exactly this in US Army photography in Flickr:

One of the unfortunate aspects of a film being so scholarly is that it adopts some of the bad conventions of contemporary scholarly politics, namely the appeal to authority. Sometimes the quotations work to make an argument, but other times they just appear as if to stand on their own, as a memorable quote from a famous writer.

Another mistake is to project the concerns and trends of the present back into history. Thus the documentary speaks of a “gender war” unfolding in Nazi cinema, as if Nazi cinema had been born in North America post-1968. If one can find a gender war in Nazi-era films, then perhaps we can find hippies too?

The documentary signals that audiences had a desire for relief and a need for distraction. But wouldn’t this then indicate the presence of at least an embryonic critique, of a degree of latent dissatisfaction? Would propaganda solve this problem, and could it? The documentary does not ask these questions.

Finally, among the flaws of the documentary we might add that too often it tries very hard to tell us what to think. Thus the narration is incessant, and even overly conspiratorial and sinister in its tone, as if the narrator were whispering a dirty secret into our ears. A number of viewers have posted comments on film review sites to complain precisely about this aspect, and how much it deeply irritated them.

However, we also learn that a totalitarian polity is nothing like a total institution: much escapes the grasp of the Nazis. In German cinema of the Third Reich there were many contradictions and ironies. There was even resistance within the mainstream.

Perhaps the best aspect of this documentary lies in the title, Hitler’s Hollywood, thus bestowing precedence and primacy to Hollywood. Given how much of “Hitler’s Hollywood” resembles Hollywood, another outcome of the film is that it ends up proving that if anything it is American society that is the regimented, totalitarian one, even as it contradicts the totalitarian nature of Nazi rule.

The problems of this film are productive problems, that serve to generate a great deal of important and useful discussion and debate. Had it aimed for greater neutrality, it might not have been as thought provoking. This documentary is ideal not just for classes in Cinema Studies, Cultural Studies, and Art History, but also Communications, Sociology, History, Political Science, and even Anthropology. Given the substantive weight of the film, its skill in condensing and representing much of what has dominated the study of cinema during the Nazi era, and the many questions that it raises and provokes, it must be awarded a fairly high score of 8.5/10.

References/Further Reading

Carr, Steven Alan. (2015). “On Doherty’s Hollywood and Hitler, 1933–1939”. Jewish Film & New Media, 3(2), 242–248.

Fraser, John. (1981). “Propaganda”. Oxford Art Journal, 4(1), 65–69.

Padover S.K. (1939). “The German Motion Picture Today: The Nazi Cinema”. The Public Opinion Quarterly, 3(1), 142–146.

Petro, Patrice. (1983). “From Lukács to Kracauer and beyond: Social Film Histories and the German Cinema”. Cinema Journal, 22(3), 47–70.

————— . (1998). “Nazi Cinema at the Intersection of the Classical and the Popular”. New German Critique, 74 (Special Issue on Nazi Cinema), 41–55.

Quinn, Anthony. (2013). “The Collaboration: Hollywood’s Pact with Hitler by Ben Urwand – review”. The Guardian, October 16.

Rentschler, Eric. (1990). “German Feature Films 1933–1945”. Monatshefte, 82(3), 257–266.

————— . (1994). “Ministry of Illusion: German Film 1933–1945”. Film Comment, 30(6), 34–40, 42.

————— . (1996). “The Testament of Dr. Goebbels”. Film History, 8(3), 316–326.

Spector, Scott. (2001). “Was the Third Reich Movie-Made? Interdisciplinarity and the Reframing of ‘Ideology’”. The American Historical Review, 106(2), 460–484.

Urwand, Ben. (2013). The Collaboration: Hollywood’s Pact with Hitler. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press.

Von Moltke, Johannes. (2007). “Nazi Cinema Revisited”. Film Quarterly, 61(1), 68–72.

Weinberg, David. (1984). “Approaches to the Study of Film in the Third Reich: A Critical Appraisal”. Journal of Contemporary History, 19(1), 105–126.

Witte, Karsten. (1998). “The Indivisible Legacy of Nazi Cinema”. New German Critique, 74 (Special Issue on Nazi Cinema), 23–30.