Cyber-Terrorism: How the US and Israel Attacked Iran—and Failed

Originally published on June 25, 2019

Sabotaging another nation’s power grids, or blowing up industrial plants, are actual acts of war under international law. The term “cyber-terrorism” as used in the title, almost softens the impact of that fact. In recent months and weeks, the US has been active—either by its own account, or according to target nations—in new acts of war that use the digital realm in order to produce concrete effects on the ground. Venezuela, which suffered debilitating power outages in March, laid at least some of the blame on alleged cyber attacks by the US. The US certainly possesses the means to engage in such cyber-warfare, and has actually done so. Iran is a case in point. Not only has Iran allegedly been targeted in recent days, it was also targeted by Obama with the aid of Israel. This requires that we review the case of the Stuxnet Worm.

Why does it matter that we should be aware and informed about the Stuxnet Worm? What is Stuxnet, and what can it do? Who has actually used it, and to what effect? What are the consequences for all of us, now that Stuxnet has been unleashed worldwide?

Americans live under a state which tells them that their country is “the target” of nefarious foreign attackers that engage in cyber-terrorism or other cyber-crimes against the US. They will rarely, if ever, be aware of the fact that it is their own country which has committed the most dangerous and widespread cyber-terrorism—and that as a result, Americans are now vulnerable to the very same computer technologies that their country first deployed against others. This is yet another instance of what others have critiqued as “American innocence”.

Zero Days (2016)

Written and directed by Alex Gibney, Zero Days (2016) is a documentary film that runs for just over 113 minutes. The film is briefly described on IMDB as follows: “A documentary focused on Stuxnet, a piece of self-replicating computer malware that the U.S. and Israel unleashed to destroy a key part of an Iranian nuclear facility, and which ultimately spread beyond its intended target”.

Alex Gibney has made several important and well received documentaries, a number of which will be reviewed on this site. He certainly is a prolific filmmaker, focusing on topics that have generated the biggest headlines, or focusing on major personalities. The fact that he is able to churn out such large documentaries in relatively short order (showing that he must be working on another film even before finishing the latest work), is a fact that has attracted some critical commentary, especially when some see work such as Zero Days being little more than a film version of the Wikipedia entry on Stuxnet. For my part, I am quite sceptical of Gibney’s political aims—at the very least, he is guilty of some hypocrisy. While Gibney is proud to showcase the fact that he sought out leakers for his Zero Days film, in order to tell us the secrets about Stuxnet, he nonetheless smeared Julian Assange and WikiLeaks for doing the same thing, only better, and on a wider range of topics. We Steal Secrets—a damning title by itself—was one of Gibney’s previous films, which of course won high praise by the media in the US. The fact that NPR has come out and positively publicized Zero Days should be a warning that we view this film with some caution. Otherwise, I will continue to view and review other films by Gibney, just as I do with other filmmakers whose productions deserved criticism.

You can view a trailer for Zero Days below:

The Sheriff is the Outlaw

The film begins with an extract from an Iranian state TV documentary that reenacts the Israeli terrorist assassination of two nuclear scientists in Iran on November 29, 2010. Voice-overs from the mainstream US media refer to the terrorism as “major strategic sabotage”. The film accompanies the Iranian documentary’s action with an Israeli speaker—an anonymous Mossad senior operative—silhouette only, voice distorted electronically, speaking to us from the shadows about the “nature of life” as being one where “evil” and “good” live “side by side”. He continues by “explaining” that there is an “unbalanced” and “unequivalent” (i.e., asymmetric) conflict between “democracies” that “play by the rules”—the rules shown include the targeted murder of scientists—versus “entities” that “think democracy is a joke”. Presumably terrorism is about making enemies take democracy a little more seriously? In other words, the opening of the film is appropriately sinister, cynical, and menacing.

There is also a certain candour to the film as presented in the words of the Israeli Mossad speaker. There is indeed an asymmetric battle. Had Iran attacked nuclear scientists on the streets of Israel, the Western media would call it a terrorist attack, and Iran would likely be bombed. Instead, Iran is just supposed to absorb Western terrorism, like Americans tolerate rain or a windy afternoon. It is somehow Iran’s natural duty to suffer us. There is also a candidly twisted interpretation of “the rules”: Western powers get to invent their own special rules, ones that are in direct violation of international law. This is what is actually meant by the “rules-based international order” slogan one hears from the mouths of Western leaders today. The sheriff is the outlaw. The punishment is the crime.

What the anonymous Mossad operative refuses to answer is whether the murder of the Iranian scientists was related to the Stuxnet computer attacks—which are the central focus of this documentary. He is followed by a whole array of experts (one of whom is Gen. Michael Hayden, former CIA and NSA director), each refusing to speak about the Stuxnet Worm, and they all seem visibly uncomfortable just for having been asked. Some explain that it is because it is “classified”. Whomever was behind the Stuxnet attack, they have refused to take official responsibility. However, what is interesting is that these individuals even refuse to simply comment on the press reports of an event that actually happened.

The narrator adds: “Even after the cyber-weapon had penetrated computers all over the world, no one was willing to admit that it was loose, or talk about the dangers it posed”. This film is an attempt to counteract the silence that has been imposed, so that it can be debated publicly.

The question posed by the filmmaker is this: “What was it about the Stuxnet operation that was hiding in plain sight?” And they suggest that maybe there was a way that the computer code could speak for itself.

How Does Stuxnet Work? Who Made It? Who was the Target?

The Stuxnet Worm, which can be delivered by a USB memory stick, is not meant to steal information. It is instead meant to cause industrial systems to malfunction dangerously, while impeding the ability to electronically monitor such systems and to shut them down before a catastrophic event occurs. Stuxnet was used against Iran’s nuclear infrastructure.

The films seeks the insight of experts at Symantec Research Labs in Santa Monica, California (Eric Chien, emergency security response), and at Kaspersky Lab in Moscow, where the filmmaker speaks with Eugene Kaspersky himself. Also at Kaspersky, Vitaly Kamluk explains that there are three principal types of cyber-attackers:

1) “traditional cyber-criminals interested only in illegal profit” looking for “quick and dirty money”;

2) activists, or “hacktivists,” hacking either for the sport of it or to promote a particular political idea; and,

3) nation-states, “interested in high-quality intelligence or sabotage activity”.

Much of the commentary from cyber-security analysts is about the size and nature of the Stuxnet code, and how they collaborated across companies to share the code and their analyses of it. We learn some interesting details here.

Stuxnet first surfaced in Belarus. Sergey Ulasen is interviewed in the film; he was the anti-virus expert who first discovered Stuxnet. Ulasen discovered it when his clients in Iran began to call him in a panic over an epidemic of mysterious computer shutdowns. The malware was first identified on June 17, 2010. What stood out about this code was its “zero days” components. A “zero day exploit,” as explained by Eric Chien, is simply a piece of computer code that allows it to spread without having to be activated by anyone. One does not need to download an infected file and run it. A zero day exploit is also defined as an exploit that nobody knows about except those who created it—and therefore no patch has been released to counteract it. There are thus “zero days [worth of] protection” against the code. Stuxnet itself contained four zero days exploits, all by itself, when typically cyber-security might find 12 zero days in an entire year, among millions of viruses. Stuxnet, with so many zero days in it, would probably fetch half a million dollars—and therefore it was unlikely to have been the product of some ordinary criminal gang, but a much more powerful entity. Eugene Kaspersky also discounts the possibility that it was produced by cyber-activists or hacktivists. A consultant in Hamburg came to the conclusion that, given the sophistication of Stuxnet, it had to be the product of at least one nation-state.

Stuxnet’s creators stole its digital certificates from two companies, both in Taipei, and both in extremely close physical proximity to each other, as Eric Chien of Symantec explains. “Human assets” had to be involved—spies—in order to extract the digital certificates, which are guarded behind multiple layers of physical security and not resting on a machine connected to the Internet.

The other significant aspect of the Stuxnet code is that it was designed to specifically target Siemens machinery, but the code analysts were not sure which kind of machinery. Then they discovered that Siemens PLCs (programmable logic controllers) were the intended target. A PLC is typically attached to large pieces of industrial equipment, like valves, pumps, or motors. PLCs are also used to control electrical power plants and power grids.

The next big discovery made by cyber-security analysts was that Stuxnet actively surveyed the systems with which it came into contact, and would run a series of checks to determine whether or not the target PLC had been reached. If it had instead come into contact with some other equipment, it would not activate. The amount of effort put into targeting one specific target, suggested to the analysts that the target had to be mightily significant.

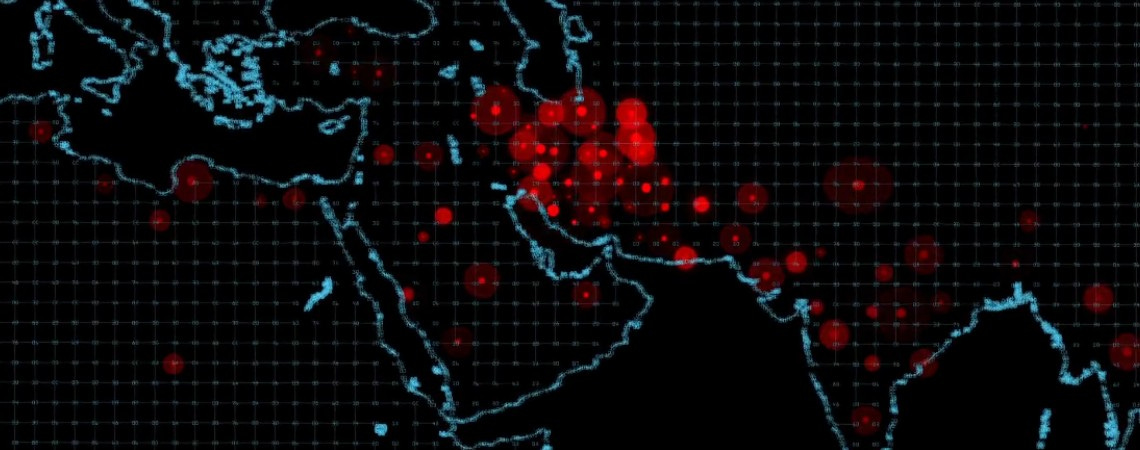

Symantec detected Stuxnet infections across the globe, since it would infect any Windows computers anywhere in the world. Industrial installations across the US itself were/are infected with Stuxnet. Cyber-security specialists were immediately alarmed about the dangerous consequences, where any power system, any industrial production, could be shut down without warning anywhere in the world. However, they soon discovered that Iran was the one country in the world that was most infected with Stuxnet, and this immediately suggested that Iran was the prime target.

To make sense of their findings, the code analysts had to turn to what was making the news, geopolitically. They learned that a number of sensitive oil and gas pipelines coming into and out of Iran were mysteriously exploding. There had also been assassinations of nuclear scientists.

The next advance came in identifying the exact industrial control systems that were being targeted, since the PLC identifier numbers were embedded within Stuxnet’s code. That is when they discovered that the targets were frequency converters from two specific manufacturers, one of which was in Iran. Since the frequency converters were export-controlled by the US nuclear regulatory commission, this told the analysts that the target in Iran was a nuclear facility.

One of the distinctive features of Stuxnet was that it lacked a “call back” component that would enable direct instructions to be given by an operator to the infecting program. Stuxnet was thus fully autonomous. Stuxnet was fashioned to unfold in a facility such as Iran’s Natanz nuclear facility, which is entirely unconnected to the Internet—it is an “air-gapped” facility. However, as no computer system is ever truly and fully air-gapped, as long as new code and new equipment is being introduced, vulnerabilities remain. NSA sources in this film state that the CIA and/or Mossad used “human assets” to infiltrate Natanz. The way that was done was to infect various industrial plants that serviced Natanz, so that contractors would unknowingly carry Stuxnet on a USB key into the facility at some point, to either conduct a software update or introduce new code.

Iranian Nuclear Development

Leaving aside the cyber-security world, the film turns to David Sanger of The New York Times, who was investigating the intersections of cyber-crime, espionage, and nuclear weapons. The emergence of the code alerted Sanger to the fact that an attack was underway. Sanger found Israelis and Americans who were involved in either building a piece of Stuxnet, or who had witnessed its construction—the first big cyber-weapon to be used for offensive purposes. Sanger investigated the history of Iran’s nuclear program, noting that Iran obtained its first nuclear reactor from the US itself, during the reign of the Shah.

The film then detours into a retelling of the history of Iran’s nuclear development, and its alleged interest in acquiring nuclear weapons. This was a troubling part of the film: given that this film is aimed at Western, primarily American audiences, speaking to them through a language and set of narratives that are familiar to them, Gibney seemed to be framing Iran as a valid target deserving of US aggression. Iran is shown as the potential “danger,” ironic given the history of US interventions and invasions in that part of the world.

Note also that virtually all of Gibney’s “expert” sources on Iran consist of former US intelligence operatives and military officials—we thus hear from Gary Samore, WMD “czar” from 2009 to 2013, and Rolf Mowatt-Larssen, a CIA officer from 1982 to 2005, among others, including Israeli officials. Totally absent from the discussion is anyone in the Iranian government, or anyone in Iran. The president of the American Iranian Council is interviewed, somewhat mitigating the otherwise complete voicelessness of Iranians. Interestingly, he explains how stringent the International Atomic Energy Agency’s monitoring regime has been, clearly suggesting that Iran was not in violation of its international agreements since it was being thoroughly supervised. He also explained that, under international treaties, Iran has a right to develop nuclear energy. Thus the president of the American Iranian Council ends up being the one moderating voice that offers a little balance in the film, and he is a particularly articulate and intelligent speaker.

However, the problem is not with who supervises the weak, but the fact that no one supervises the strong. The film sometimes seems to miss this basic point, especially by framing Iran as a dangerous nuclear threat.

A Scandinavian former IAEA inspector—who in the film says that he has been to Iran both very few times, and very many times (just one sentence apart)—claims that the agency found residues of weapons-grade uranium (isotope 236), which suggested that Iran had imported it from Pakistan, possibly through the black market.

The one significant observation that arises is that if Iran sought to build nuclear weapons, it was in response to the US invasion of Iraq as part of Operation Desert Storm in 1991. This demonstrated to Iran the extent of the threat posed by the US to even the most formidable militaries of the region, and thus the need for an extra layer of defense. Iranian fears were further amplified with the direct threats made by George W. Bush from 2002 onward, when he labelled Iran as part of an “axis of evil”. If this argument is correct—the film tends to present speculation from US officials as incontestable fact—then Iran was certainly justified and its response was both reasonable and wise. Indeed, the real mystery is why Iran would not pursue, or is not pursuing nuclear weapons development.

The Cyber Option and Israel’s Role

What led to the deployment of Stuxnet? By 2007/2008, the Bush administration was bogged down in Iraq and Afghanistan, and after the WMD fiasco, the film narrative suggests, Bush was not confident about openly challenging Iran over its nuclear program. According to one of the film’s sources, Condoleeza Rice essentially told Bush, “you know, Mr. President, I think you’ve invaded your last Muslim country, even for the best of reasons”. Bush also did not want to let the Israelis attack Iran, since that would have immediately drawn the US into war with Iran. In fact, as Gen. Michael Hayden attests in the film, Israel lacks the independent capacity to launch and sustain a military attack on Iran without US assistance. General Hayden then adds an astute observation: “there would be many of us in government thinking that the purpose of the raid wasn’t to destroy the Iranian nuclear system, but the purpose of the raid was to put us at war with Iran”.

Another key point made by Hayden in the film is that the Bush administration wanted to avoid a situation where a future president was reduced to one of only two options: either bomb Iran, or Iran developed a nuclear bomb. This seems to be the corner into which Trump is painting himself.

Since the US, under Bush, was not willing to engage Iran in a direct military confrontation, it was the Israeli government under Netanyahu that proposed an alternative means to attacking Iran. A joint group of Israeli and US intelligence officials then advanced the idea to Bush of devising and deploying what came to be known as the Stuxnet worm.

One of the mistakes made by Iran was the publication of a large number of photographs showing Mahmoud Ahmadinejad touring the Natanz nuclear facility, in the company of numerous key scientists—thus inadvertently aiding Israel in its targeting. One of the scientists appearing in a photo standing behind Ahmadinejad, was assassinated a few months later. Another thing shown by the photos were computer screens displaying arrays of centrifuges that were being monitored. The array of centrifuges showed six groups, each group with 164 items—numbers that perfectly matched what was found in the Stuxnet code. Thus the photos seem likely to have aided the process of devising the attack code.

The Attack

Centrifuges for enriching uranium contain rotors spinning at the speed of sound, with some parts of the centrifuge made of carbon fibres (which shrink with heat), and other parts made of metal (which expand with heat). Maintaining the integrity of a centrifuge is thus delicate and sensitive. Iran’s centrifuges are proudly featured every April for “National Nuclear Day”. The IAEA inspector in the film is particularly impressed with the complexity, professionalism, and sophistication of Iranian facilities. Iran’s centrifuges were specifically targeted by Stuxnet.

How Stuxnet actually operates is graphically demonstrated in the film—and for me, this was the most memorable feature of the documentary. See the extracted clip for a complete demonstration:

The demonstration aside, what Stuxnet was designed to do was sit and wait within the Natanz nuclear facility, and to record and save all operations. Once the required amount of time had passed for the full cascade of centrifuges to be filled with uranium being enriched, Stuxnet would then activate. Its first step was to vastly increase the revolutions of centrifuge rotors to the point that uncontrollable revolutions would rupture the centrifuge. The second step was to block any communication of an emergency to the controllers, by reproducing the old data that it had recorded. The third step was to prevent the controllers from shutting down the centrifuges, by disabling all the kill switches.

The only cyber-security specialists who appears resistant to attributing Stuxnet to the US, is the US-based analyst at Symantec, Eric Chien. He does make the valuable point—one deliberately sidestepped by the US media and US politicians—that attribution is very difficult to make, and the traces that lead back to a supposed origin can be faked. (The assertion made by US intelligence agencies about having evidence suggesting Russian hacking was thus always, at best, highly dubious from the outset.)

The Voice of the Leakers

To ascertain the facts of US and Israeli collaboration in the production and use of Stuxnet, Gibney avails himself of leaks and whistle-blowers in Washington, DC. (It’s only permissible to do so when Gibney does it, unlike his treatment of WikiLeaks’ Julian Assange who did the same.) Gibney comments: “while D.C. is a city of secrets, it is also a city of leaks. They’re as regular as a heartbeat and just as hard to stop”—which again underscores the opportunism of his critique of WikiLeaks in another of his films.

Gibney’s anonymous sources, compiled into one fictionalized character speaking in the film as if she were a hologram, testify that “we” created Stuxnet (“we” was undefined at that point). At the same time—and this strained credulity—these intelligence operatives somehow felt remorse because “we came so fucking close to disaster,” and for some reason, on this subject alone, it is necessary that the intelligence agencies “get the story right” for the public interest. It seemed a like a charming idea: democratic accountability—all of a sudden. It’s possible, but also suggests we interpret their statements with due caution.

Gibney’s sources claim that Stuxnet was the product of a huge “multinational, interagency operation”. The agencies were the CIA, NSA, the Pentagon’s Cyber-Command; in the UK, the GCHQ; “but the main partner” was the Israeli Mossad. The technical work was done by Mossad’s Unit 8200. Now the narrative shifts: “Israel is really the key to the story”. Another source claims that “much of the coding work was done by the [US] National Security Agency and Unit 8200”.

Further bolstering the case against the so-called “Libya model”—ending a nuclear weapons program, disarming, and transferring all materials to the US—this film’s anonymous NSA sources testify to Libya’s centrifuges (P1s) having been studied at Oak Ridge National Laboratory because they were the same kind in use in Iran. Having Libya’s equipment allowed the US to use the items to help engineer Stuxnet, or what the NSA and Cyber-Command called “Olympic Games” or OG. The Israelis also did tests using the Libyan P1 centrifuges.

The US: Against International Law

Through espionage, the US also obtained the plans for Iran’s newer centrifuges, the IR2s. In the tests run by the US, they were able to explode the centrifuges by manipulating the rotors. After inviting President Bush to examine shards of the destroyed centrifuges, he reportedly approved the use of Stuxnet. There were no reported concerns expressed by anyone in Bush’s cabinet about the fact that using Stuxnet would constitute an undeclared act of war.

To avoid any legal troubles with the incoming Obama administration, operatives under Bush installed a kill date in the Stuxnet code (January 11, 2009). This was just days before Obama’s inauguration. The desire to bring the operation to a close before Obama’s team took over, is at least tacit recognition of the illegality of the program. Of course, Obama reauthorized the program within his first year in office.

Obama was devoted to cyber-“defense” to protect critical infrastructure in the US—which actually meant he was committed to offensive operations aimed at paralyzing other countries’ critical infrastructure. One can never escape the American international modus operandi of inversion and projection. In fact, the overwhelming majority of cyber-spending under Obama’s budget was devoted to the development of cyber-weapons for offensive purposes.

Under Obama, a whole range of new and powerful cyber-weapons were to be developed. Stuxnet was just the opening shot.

International law, with strict reference to the use of cyber-weapons, is “written” by custom, as explained by a US official in the film. Customary law requires a nation-state to at least say what it did, and why—which the US will not do. Thus the norm has become: do whatever you can get away with doing. This is a world which the US has created, as much as it cries innocence today.

Initially, Stuxnet was deemed a success. Centrifuges did blow up in Iran’s nuclear facilities, a fact verified by IAEA inspectors. Whole groups of centrifuges were dismantled, and a number of nuclear scientists were fired. There were other consequences, as will always be the case, which the US could not control.

Coming Home to Roost

After the attack, Obama only then began to worry about how Russia and China could do the same to the US, with the added justification of the precedent set by the US itself. Obama knew that word would get out eventually, as it did. Nonetheless, Obama persevered with the program.

Another problem with Stuxnet is that it was spread all over the world, infecting all sorts of machines, just so the US and Israel could get at their Iranian targets. The charge made by NSA sources in the film is that the Israelis took the US code, changed it, making it much more aggressive, and then launched it without US agreement. These sources, (feigning?) great indignation at the rude and inconsiderate Israelis, contradict earlier claims in the film that Stuxnet was approved for use by both Bush and Obama.

By spreading far and wide, the Stuxnet code ended up in Russian hands, where Russian state security experts could study it and potentially use it, while Iran itself also did the same. Unlike other weapons, when cyber-weapons are used they can be apprehended intact on the receiving end. The Department of Homeland Security, supposedly unaware of what the NSA and CIA had done, grew alarmed when it encountered the Stuxnet malware, and its potential to do massively destructive and lethal damage in the US itself. The DHS Cybersecurity Director, Sean McGurk, who speaks in this film, was not aware that he was dealing with a possible case of the chickens coming home to roost. Likewise, Senator Joseph Lieberman, on the Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs Committee, appears in Senate footage asking—apparently innocently—about the origins of Stuxnet, and if a nation-state was behind it…not knowing that it was his own. Of course, what the film does not raise is the question of whether this was all theatre, to cover for the US violating international law and engaging in war against Iran.

David Sanger says in the film:

“the United States government has never acknowledged conducting any offensive cyber attack anywhere in the world. But thanks to Mr. Snowden, we know that in 2012 president Obama issued an executive order [Presidential Policy Directive 20] that laid out some of the conditions under which cyber weapons can be used. And interestingly, every use of a cyber weapon requires presidential sign-off”.

Given the extensive over-classification of information on the US role in producing and using Stuxnet, and the fact that every US government official interviewed or shown in the film denied any knowledge of US involvement, no real public discussion can develop. This in itself does further harm to democracy in the US. Even the former NSA and CIA director, Gen. Hayden, criticizes over-classification in his interview for this film.

Rather than invite public debate, the Obama White House went after the whistle-blowers, going as far as targeting Gen. James Cartwright, Vice Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, in a criminal investigation. The US and Israel have yet to acknowledge the existence of the operation, to this day.

The Failure and the Response

On top of everything else, Stuxnet did not make a huge impact on the Iranian nuclear program. In fact, the tiny dip in the number of centrifuges caused by Stuxnet, was counteracted by a vast and rapid increase in the number of centrifuges installed by Iran, along with new nuclear facilities. Iran’s nuclear program became even more advanced, even as it suffered every single known coercive action thrown at it by the US and its allies, short of direct combat.

The US is itself highly vulnerable to cyber attacks. US attacks on Iran encouraged Iranians to form a Cyber Army to fight back. Iran now has one of the largest cyber-armies in the world, according to the president of the American Iranian Council. Stuxnet did minimal and temporary damage to Iran, yet unleashed a wave of responses that showed how use of the cyber-weapon was a major strategic error.

Iran launched two attacks against the US, according to Richard Clarke in the film: first, Iran attacked ARAMCO in Saudi Arabia, the world’s largest oil company, and they erased all software, every line of code, from about 30,000 computer devices; second, Iranians allegedly launched a surge attack on US banks. The clear message was that, if provoked further, Iran had it within its means to disrupt the US financial system and the world energy market.

Had Iran not responded, the US apparently had a much larger plan (“Nitro Zeus”) for total cyberwar against Iran, which included shutting down its power grids, disrupting military and civilian communications, and disabling defenses.

Conclusion

There is a great deal of information in this film that would be interesting to those who are new to geopolitics, but that is also largely peripheral to the film’s core story. Thus a lot of time is spent (wasted) on self-flattering operational histories told by Israeli fighter pilots and US spies, or a New York Times journalist reciting the most basic essentials of his published stories, or American government officials presenting their preferred version of Iranian history. On the whole, the film is about one full hour too long, and it can make for long stretches of tiresome viewing of tendentious material.

This film would be appropriate for courses in International Relations, Political Science, Middle East Studies, and any courses dealing with US intervention and/or cyber-terrorism. Generally, the more critical reviews of this film are on solid ground, particularly those targeting the film’s deficit of any new information, and the fact that it provides very little that is not already covered by books, news reports and even Wikipedia. The visuals in the film are mostly limited to talking heads, news footage from Iran, and endless animations of layers of computer code—visually, it is not a very engaging or memorable film. However, given that the film can provoke numerous important questions and in some cases provides some very interesting answers, plus the fact that it effectively condenses available knowledge, it merits a score of 6.75/10.