In Part 1 we ended with the documentary’s discussion of the type of business model that has been created around COVID-19, or to match the title of the film, a system. The system consists of interlocking and mutually enforcing actors, institutions, and processes:

Government, working in tandem with establishment scientists, transnational business interests and the media;

The dominant parts of the scientific establishment working with policy-makers, major pharmaceutical companies, and the media;

The media, which exclusively repeat only what government sources say, without question normally, and which only feature establishment scientists who push the same agenda as government;

Transnational corporations, whether retailers or pharmaceutical giants, who directly benefit from the government policies which they themselves shaped via supporting scientists and the media.

This is just the most basic outline. What follows is a more complete and detailed picture.

Pharmaceutical Profiteers

Dick Bijl, President of the International Society of Drug Bulletins, a doctor and epidemiologist as well, appears next to Nico Sloot in a conversation about the profit model of the pharmaceutical industry. Of course pharmaceutical companies are driven to maximize profit, Bijl agrees, but, “if that benefited people’s health, you’d say: fair enough, who cares”. The problem Bijl notes is that one cannot make a strong case that medicines are having a positive impact:

“there are increasing signs that medicines play a key role in the falling life expectancy in the United States and stagnating life expectancy in the European Union. We’ve seen big scandals around Vioxx, Rofecoxib, a simple painkiller. The medication for diabetes: rosiglitazone, Avandia. Countless medications have cost hundreds of thousands of people their lives. It just keeps on going. You would think that after all of those tragedies the rules would be tightened. They’re not. In fact, they’re being relaxed”.

Bijl faults the European Medicines Agency (EMA), and the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), for doing too much to facilitate drug companies and not enough to put citizens first. He notes how the FDA says very clearly that it wants to help manufacturers to bring their products to market.

He then goes through an extensive list of prohibitively expensive drugs (produced at low cost), and their negative side effects, or, their proven inability to cure sickness. Here Bijl singles out Remdesivir and notes how it had been given provisional approval during the coronavirus pandemic, despite the notoriously shoddy research on which the manufacturer, Gilead, based its claims. Notably, Anthony Fauci openly promoted Remdesivir, hailing as “proven” that “a drug can block the virus,” adding that Remdesivir set a new “standard of care”. Fauci used the White House itself as a photo opportunity to make this promotional announcement. Shares in Gilead immediately rose 5% in value. Remdesivir’s trials were sponsored by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) led by Fauci, under the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Separate from this film, yet directly relevant, is a powerful catalogue and cutting analysis of the deeply troubling facts about the UK that answers the question of cui bono? Bijl above might not be the one to make such an argument, but there is more than enough circumstantial evidence to avoid missing some classic parallels between today’s state “protecting citizens” and basic racketeering of the kind described by Charles Tilly.

“…but my doctor said I should get vaccinated…”

Bijl also targets companies such as GlaxoSmithKline and in particular AstraZeneca, for their scandal-strewn histories. In the background we see a news report about AstraZeneca being fined $5.5 million for bribing doctors in Russia and China. (AstraZeneca, Johnson & Johnson, and Pfizer also donated massive campaign funds to key members of the US Senate Finance Committee.) Key names of pharmaceutical companies that are today leading in COVID-19 vaccine sales, have also been found guilty of healthcare fraud. Shown in the documentary is this New York Times article, which opens with this:

“AstraZeneca, the large pharmaceutical company, pleaded guilty today to a felony charge of health care fraud and agreed to pay $355 million to settle criminal and civil accusations that it engaged in a nationwide scheme to illegally market a prostate cancer drug….”

AstraZeneca was found guilty of bribing 400 doctors across the US to induce them to prescribe Zoladex. “Those inducements included thousands of free samples of Zoladex, worth hundreds of dollars each,” which the physicians then billed to Medicare. AstraZeneca also “gave doctors financial grants, paid them as consultants and provided free travel and entertainment”.

Doctors, for their part, often do not have sufficient expertise to evaluate research behind particular products, and Bijl says that doctors are often susceptible to marketing by pharmaceutical companies. Doctors often take at their word the various medical sales representatives sent out by these companies. Medical opinion leaders also play a key role in marketing particular drugs, and they have a reach that extends into ministries of health, parliaments, and so on.

Nico Sloot criticizes the lack of liability for pharmaceutical companies—particularly for vaccine producers today—and the secret deals that they previously signed with governments. In The Netherlands, incredibly, the government has agreed to pay any claims that may be lodged by people who suffer severe effects from vaccines. In other words, taxpayers are covering liability for vaccine producers.

Vaccine Hesitancy or Vaccine Rationality?

Today, too many in the media and academia, not to mention the WHO, treat “vaccine hesitancy” as a problem. The WHO, which receives funding from vaccine producers, even listed “vaccine hesitancy” as one of the top ten public health “threats”.

For Sloot, what is called “vaccine hesitancy” is not a problem, but really more of a solution. As I understand, it is a solution because it can involve a heightened awareness, and rationality, of the secretive and profit-motivated complex that binds vaccines to state-directed policy. Reducing “vaccine hesitancy” to “fear,” or to some amorphous “life experience,” is simply a way of insulting people while pretending to “understand” them. More importantly for Sloot, vaccination is simply not needed for healthy people with functioning immune systems, for all of the reasons listed in Part 1.

Contrary to Bill Gates, and his calls for the total vaccination of the world, Sloot argues that “we don’t need vaccinations, but a solution to the coronavirus problem”. The problem is not vaccine hesitancy, but an overreaction that generalizes from people with low immunity, to all people.

To make his argument, Sloot points to statistics that are almost perfectly mirrored in Quebec, as almost everywhere else. Here are some relevant statistics for Canada, Quebec specifically, and then Trinidad & Tobago (the three that personally interest me the most):

Canada, with a population of 35 million (in 2016), has had to date a total of 1.374 million cases and 25,440 deaths. In other words, 3.92% of Canadians had COVID-19 at some point, according to test results. Deaths accounted for 1.85% of all COVID-19 cases, thus 0.072% of the total Canadian population.

In Quebec, 32.2% of all COVID-19 deaths were people aged 90 or more; another 39% were those aged 80-89; and 19.3% were those aged 70-79—the combined total of these three age brackets is 90.5% of all deaths.

Also of special interest to me, Trinidad & Tobago, does not even now represent an extreme picture: with a total population of 1.4 million, it has had to date 22,620 cases—or just 1.6% of the population has been infected at some point. Of all persons tested for COVID-19, 12.6% tested positive . The number of deaths, at the time this was written, was 458. Deaths account for 2.02% of everyone infected with COVID-19. Of the total population of the country, COVID-19 deaths count for 0.0327% of the population. Thus even in Trinidad, where hospitals are under severe strain and treatments are limited, death among the infected is still extremely rare—which nonetheless is surely no consolation to their loved ones.

Sloot argues that, instead of vaccines, the effort should have been directed at protecting the most vulnerable, and to have the right medication for them. Meanwhile, take all the time needed to develop a safe vaccine. As he says: “Surely we won’t use a pressure-cooker situation and business models to quickly produce a vaccine for the whole of The Netherlands, for healthy people? I don’t get it. It’s not right”.

The Media and the System that Manipulated a Crisis

The media come in for much needed criticism. In The Netherlands, as in Canada, the US, and apparently most other countries, the situation is best described in the film by the endocrinologist, Evelien Peeters: “Over the past months the media have headed in a very specific direction. We’re being told news in a very one-sided way”. One-sided editorializing is not usually called “news,” but is more commonly understood to be propaganda.

Sloot plays back an interview with the editor-in-chief of the biggest newspaper in The Netherlands, who asserts that it is the duty of the press in a pandemic not to question, not to critically analyze decisions and consequences, not to dispute statistics. Sloot here refers to Pieter Klok of De Volkskrant newspaper. On Radio 1, Klok stated:

“With so much fear around, we need to speak with one voice….when society is so afraid, we need to agree with each other….You can’t expect everyone to make up their own minds….It’s wise for a country to choose one path, and for us to support it”.

Klok was clear that now was not the time for the media to raise questions either about the consequences of policies, nor to even mention the fact that disagreement prevails among virologists. Members of the public should not have a wide range of information, and be left to make up their own minds. This was “journalism” during the pandemic—whether private or state-owned media, it made no difference.

Those with an active interest in the field of cultural imperialism will be happy to see Cees Hamelink, Emeritus Professor of International Communications at the University of Amsterdam, appearing in this documentary. Hamelink agrees with Sloot that the media today have failed miserably in acting as an independent and critical source of information, and that press conferences typically feature journalists as willing accomplices of the state. He then adds: “We, the vast majority, the ordinary citizens, are not represented. There’s no lobby for us”. This is a comment on the diminished state of democracy in the West. The impoverished quality of the media is to be found in its lack of knowledgeable, well-informed, and critical professionals. With an impoverished media, democracy is impoverished because the “media” are intermediaries between reality and the people, as Hamelink explains in the film.

Hamelink presents a useful theoretical perspective on the systemic manner in which this crisis has been produced, and it consists of two parts. One part has to do with rationality: reflecting on decision-making in areas such as politics and economics, what prevails is what psychologists call a “bounded rationality,” that is, a limited ability for rational thought and action. The result is that either the political decisions were irrational, or when they were occasional rational they failed to move a public which had a similarly limited capacity for rationality. This reminded me of Pierre Bourdieu’s approach, noting that what prevails is not rationality as such (with all the conscious self-reflection and calculation that implies), but rather “reasonableness” (what seems “right” within the cultural confines of a specific society).

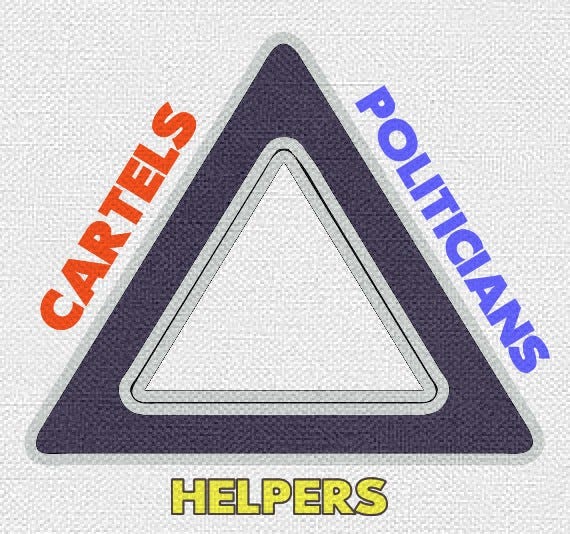

The second part of Hamelink’s quick excursion into theoretical analysis in this film involves the triangle that constitutes what he sees as the COVID-19 system. Hamelink explains what makes up this triangle: “It consists of the cartels, clearly defined and with a clear agenda, and the political decision-makers, and the helpers”. The cartels in this case are the large transnational firms, pharmaceutical companies, online retailers, and financial interests. The cartels exercises influence on politics through lobbyists. The politicians, in Hamelink’s view, “muddle along” and work in a “grey zone” of determined ambiguity, of claiming to know less than they do. “And then there are the helpers, the assistants,” the third leg of Hamelink’s triangle: “those are the think-tanks, the lobbyists. Politics is driven mainly by lobbyists”. Hamelink singles out one group of “helpers”: “the key helpers in this case have especially been the media. Helpers are needed because decisions are made, not in the interests of the vast majority, but of the small minority”.

(Helpers of course include technocrats, actors such as Anthony Fauci—scientist and bureaucrat—whose connections span the political and corporate worlds. Fauci was constantly in front of the camera, speaking as if he were an elected political leader and had the final say on what hundreds of millions of people would be allowed to do, or not. Such overlaps inevitably produce a now routine phenomenon: the conflict of interest. One of the best representatives of this, in the present context, is Peter Daszak and his EcoHealth Alliance. Daszak has been responsible for both “investigating” the virus’ alleged origins as the only US member of the WHO team that went to China earlier this year, and yet he was also responsible for funding gain-of-function research at the same Wuhan Institute of Virology at the epicentre of the pandemic. Daszak insists that the virus was not even accidentally leaked from a lab [which has happened several times in the last 20 years in China], but rather spread from animals to humans. He has made these claims without offering any evidence, and despite serious evidence to the contrary. Allegations of a cover-up now seem to stand on more solid ground than ever and, at the very least, such a cover-up ought to have been expected.)

Ignoring the extent of know-how that exists in a society, Sloot observed that it has been the case that governments speak to the public as if it consisted entirely of pre-schoolers; addressing them as irrational creatures is not something that can be sustained (thus somewhat departing from Hamelink’s approach). I was worried that this phenomenon, of officials lecturing the public as if it consisted of infants, was one that prevailed mostly in North America. It is disappointing to see that the pattern of infantilizing citizens, in order to rationalize discipline and punishment, is one that stretched across the globe. The message was always fear. Nico rightly observes that a particular kind of regime specializes in fear-mongering: a dictatorship.

He then asks his central question: “Ultimately, taking into account everything that’s going on here, you might wonder: is this really about public health?”

Politicians should trust society, Sloot says on reflecting on his personal experiences during the crisis. Governments need to respect people’s autonomy, and understand that we are capable of doing a great deal for ourselves and each other. Instead of trust and autonomy, governments restricted freedom. In the end, governments did massive damage: people amassed mountains of debt, lost jobs, and all of us have essentially lost at least a year of real living.

Nico asks another key question: “Why is it our policy that the only hope is a vaccine?” In making this the only hope, what other powers are at play?

Locking Down, Removing Self-Determination, Accumulating Capital

Ad Broere, an economist and author who collaborated with Sloot, appears in the film, and he shares his view on what is really happening at present:

“I think the coronavirus is just one part of an action that has now been set in motion that really just pulls the strings tighter from the position of those who are in power at the moment and who want to retain that power whatever the cost and who have certain ideas about what to do with that power. Who have a vision of humanity and the future of humanity which they want to bring about in reality. A few people are going to determine our future effectively taking away our right to self-determination, effectively leading us towards a goal set by them with no regard for us”.

Broere observes that in The Netherlands, where roughly 10% of the people own 75% of “everything there is to own”, such inequality has greatly increased during the lockdown and it is set to increase further as a result. As small businesses collapsed, and the self-employed were ruined, big business made enormous gains and will likely expand as a result of the termination of their many smaller competitors.

Sloot then mounts a very effective presentation, showing the distribution of wealth in the European Union. Focusing specifically on The Netherlands, he notes how it took eight years to deal with the aftermath of the 2008-2009 financial crisis, with the bailout of the financial sector costing the country about 50 billion Euros and the cost was borne primarily by working citizens and small- and medium-sized enterprises. However, The Netherlands has now added about 100 billion Euros in debt to deal with the effects of the lockdown. The last crisis (2008-2009) resulted in hospital beds being cut from 2,200 to 1,100 in the country. One can only imagine what the next set of cuts will bring. If the last crisis took eight years to pay off, then it’s possible that the latest one could take 16 years (more or less).

The biggest winners are the massive corporations that have hoarded most of the wealth in the world, Broere explains, and that essentially pay no tax because they have countless ways of avoiding taxation. The new debt acquired by states will be paid by workers and small- and medium-sized businesses—and therefore, as Broere states, citizens themselves have “been given as security for the repayment of the debt”. No wonder the state now suddenly seems so desperately concerned about our state of health.

Broere then presents a broader argument:

“If that money were freed up we’d have no more poverty in the world. That poverty is deliberately maintained. It is maintained based on the fact that we have a system in which self-interest and greed and power-seeking are rewarded, facilitated. I don’t see the people in those positions who are so incredibly rich, with a few exceptions voluntarily giving up that position. It’s not even about the money. It’s purely about the position of power. Because power corrupts and a lot of power corrupts massively”.

Yet here were the media, featuring Bill Gates as if he had special expertise in managing viral outbreaks, speaking without anyone demanding to know if he would surrender a portion of his many billions to make sure that the mass of the global population would not suffer immense loss from the lockdowns. The same Bill Gates, with his investments in healthcare and biotech companies. Think of Amazon: people who did not know any better, or did not stop to think, flooded Amazon with orders during the lockdowns thus feeding the very monster that was rising as one of their greatest enemies.

Ultimately, Broere’s argument is a revolutionary and historical one. He emphasizes the need to end the current financial system that was set up at least three centuries ago to benefit the ruling class, particularly the nobility:

“We need to get rid of this system. This financial system took shape over three centuries ago. It was set up in the interests of the ruling class. It was set up as a system to make money available for the kings and the nobility so that they could finance their operations and finance their lifestyle. It was never actually meant for the people. The people were the ones who had to pay off the debts incurred by the king and the nobility. We need to get out of this system and move to a different one. Because the system we’re in now is simply not good for us. It’s a destructive financial system. I think people should do their own research and make the link between what we’ve discussed now about money and power and positions of power and what’s done with them and the effect that has in society and in politics”.

Who Rises Victorious from this Rubble?

Another intriguing point conveyed by Sloot involves the idea that, “we’re transitioning to biotech and data technology….when you move into a new age a power vacuum of sorts occurs”. He argues that the powers pushing the latter, the new system of accumulation, are also looking to create a new social structure. In this vein Sloot converses in the film with Bob De Wit, Professor of Strategic Leadership and Digital Transformation at Nyenrode Business Universiteit. De Wit’s argument is that we are currently in a vacuum, an intermediate zone between the industrial age and the digital age. In the process we can already discern the outlines of emerging “corporate states,” as De Wit calls them. De Wit’s argument is that because they have amassed such spectacular wealth, these global giants also have more power than states. Then De Wit modifies his argument, and says that such corporate giants are more powerful than most states (clearly implying not all states). This is an important, but too subtle concession: his argument is that “in the past,” rules were made by countries, societies, and politicians, and corporations had to adapt to the laws of states—but apparently that is less true now.

De Wit explains that in this age of transition, there is heightened turmoil and instability as new rules are being created—and the coronavirus is the least of our problems, he adds. De Wit cautions that as long as we allow ourselves to be divided, we will not be able to challenge these new powers and create a better society. But he also speaks of the extreme inequality that exists in societies around the world, and how it is increasing, and that this can lead to a revolution. So it is not the case that “corporate states” will automatically achieve hegemony.

The other outcome is hegemonic corporate states, that resemble feudalism. In other words, a society exclusively dominated by elites, with ordinary “citizens” left to fend for themselves.

What The Netherlands shows, however, is a situation where bottom-up citizens’ movements have formed (Sloot’s own team is an expression or nucleus of such a movement), uniting workers and entrepreneurs in a counter-movement against domination by new elites. De Wit is fairly confident that a civil majority will win in such a struggle, if an anti-elite counter-movement forms of sufficient size. Some people, even those who consider themselves “leftist,” are blindly denouncing such movements using the elitist, derogatory label of “populist” to name such movements. To overcome such divisions, De Wit offers a refreshing, very human perspective:

“if we can create a civil movement that says: ‘We don’t want this. We want to get back to what matters: to friendship, being close, having fun, having parties, normal human things. If we all agree that we want to go back to a humane society, that movement can provide opposition. The good news in all this is that the technology we’re talking about—digital technology, biotech, a number of technological developments—the platforms you mentioned, blockchains, artificial intelligence…they can make the elite more powerful but they can also empower the citizens. The technology is neutral, it depends on how we use it. We can use technology to create a decentralized, local economy”.

De Wit also ends up calling for a new economic model, one that supersedes the old industrial model—the passage of which Sloot appeared to bemoan as he took us to meet De Wit.

De Wit’s explanation can prompt us to ask a number of questions. Instead of Hamelink’s triangle, De Wit essentially has a single line, where “helpers” assist in the formation and maintenance of what is now a fusion of cartels and governments. Two other issues raise questions.

First, is there an opposition between industrialism and digital technology? Is there synergy between the two? Digital technologies cannot even materialize without infrastructure, energy, mining, and manufacture. On the other hand, there are differential levels of remuneration for value added activities, which appear to tilt in favour of digital enterprises (yet this documentary shows that pharmaceutical companies have the highest rates of return). It may be the case that what De Wit is implying is that industry (mining, manufacturing, etc.) as we have known it in the past, is no longer a securely autonomous and commanding economic force that can be relied on to stabilize a social order; instead, industry now serves in a subservient position as an adjunct to the digital economy.

Second, one could well argue that until we meet a corporation that is itself a military superpower, no corporation has any real power to impose itself over all states, to exercise coercion as a last resort. To make new rules, corporations have to lobby and purchase access to politicians and governments—they have to plead with “old” states. Corporate giants have to essentially rent the power of states to enforce a world order that favours corporations. Even a corporate behemoth (like Amazon) lives in mortal terror at the prospect of even limited unionization; it has not transcended the rules of the old state.

Large corporations certainly can “behave like states,” to use De Wit’s words, and create their own rules and conditions—but is that new? Some African nations were colonized first by corporations (backed by imperial states). As I posit in my Political Anthropology course, we can discern two major formats for power in our society, that is, two institutional pillars that parallel each other and often work in tandem: political parties and corporations. Political parties are the corporations of the public sector; corporations are the political parties of the private sector. Hamelink’s “helpers” usually mediate between the two.

Where De Wit’s arguments seem to work best is when corporations deal with very weak states of the Periphery, states that have been already weakened by the rules, conditions, and pro-business impositions of powerful states in the Centre. In the aftermath of structural adjustment programs, of course a Jamaica or a Fiji will look significantly weaker when dealing with a Unilever, ExxonMobil, or Facebook. But as Facebook and Google are learning, even semi-peripheral states can impose their demands (even when their actions fall far short of nationalization); states can impose limits, regulations, and fines—and in recent cases Facebook and Google have been forced to concede to states.

Where De Wit’s argument could have been strengthened is if he noted that corporations are no longer satisfied with renting or purchasing access to state power: they now actively seek direct power in existing states. Hence the various “Goldman Sachs administrations” in the US, where an inordinate number of executives of that firm have won key positions in cabinets. The same could be said for numerous other revolving doors, such that it is hard to tell where the state ends and where Google or Raytheon begin. But is this new? Think of the extensive overlap between the Eisenhower administration in the 1950s, and the United Fruit Company—and even before then, stretching back at least to the mid-1800s, the dominant influence of railroad, tobacco, cotton, and oil magnates. If, as some Marxists have held, the state exists to serve and protect capital—then we have never had modern states that were insulated, protected from, or autonomous from capitalist interests.

In the end, De Wit and Broere are certainly onto something essential here, which puts the coronavirus much lower in our list of concerns, and refocuses our attention on capitalism.

Ruling Workers and Ruining Workers

Sloot then goes to Italy to speak with Dutch correspondent Angelo van Schaik. He begins by speaking of how hundreds of thousands of people unemployed because of the severe lockdowns in Italy, either never received promised financial support from the state, or it came months later—their money was “lost” in the bureaucracy, and many had to make do without unemployment benefits. During the “second wave,” many Italians—quite reasonably—became impatient with new restrictions, because their financial situation caused much more anxiety than the virus itself. Demonstrations occurred almost daily, and some became violent—the desperation was palpable. There has even been a rise in hunger. (In the US, some particularly insensitive, callous, and obviously comfortable pro-lockdown activists called such concerns “selfish”.)

The Science/The Silence

Toward the end of the documentary Sloot points out a very basic and crucial fact: doctors and scientists without connections to big pharmaceutical companies were generally those we did not hear or see in the media—they were routinely sidelined, ignored, or worse if they had contrary perspectives. We must remember that this happened in this “pandemic,” especially whenever dominant elites invoked “THE SCIENCE”.

“The science” was really the silence: the silencing of a much needed diversity of expertise to inform and guide our decisions. THE SILENCE has been far more oppressive, a smothering force, than the virus itself ever could be. Here Sloot lists in quick succession the names we typically heard, all with connections and interests vested in the pharmaceutical industry: Christian Drosten (PCR testing); Anthony Fauci; Neil Ferguson (discussed in a previous review); Ab Osterhaus in The Netherlands (also mentioned before here). Sloot then points to how questionable this situation is: “I don’t understand why, when we seek advice about public health, our health, these are the kinds of people that are chosen to tell us what we should do”.

Nico Sloot almost closes the documentary with these vital observations:

“If you scare people enough, they can’t think straight. This experiment in fear has been going on for seven months now. It will be a big problem trying to reverse that in due course. It’s not going to be easy. If we’d acted on what we found out at the end of April, we would have incurred under a third of the debt we have now, maybe even less. We would have had fewer deaths too. We would have protected care homes right away, where most deaths occurred. They’re doing it again in this second wave: fear, panic, a kind of experiment—just because the ray of hope is a vaccine. That’s the cause of all the trouble”.

When a Syndemic is Treated as a Pandemic

Sloot, citing an article in The Lancet which made an argument similar to that of his team’s, noted that what we have now is not exactly a “pandemic,” but rather a syndemic. A syndemic involves two coexisting conditions that can interact with and even exacerbate each other. On the one hand, we had COVID-19, but on the other hand there was the force of existing underlying conditions or comorbidities such as: cardiovascular disease, cancer, diabetes, and lifestyle diseases mainly related to obesity. It has been a case that the nearly all deaths were a result of COVID+comorbidities, i.e., a syndemic.

This is a problem: we have been treating a syndemic as if it were a pandemic. In this syndemic, only about 2% of people, at most, are truly vulnerable. The concept of “pandemic” generalizes; the concept of “syndemic” specifies. A pandemic suggests general danger, a universal threat, and it inflates numbers (its favourite statistic being “case numbers”)—thus Dutch Prime Minister Rutte described Holland as “gripped by coronavirus,” and he predicted “a large part of the population will be infected”. A syndemic, on the other hand, demands more rationality and precision, and its numbers are far lower (focusing on hospitalizations and deaths). Not having properly identified the problem to begin with, we could only arrive at the wrong conclusions based on erroneous assumptions, and disastrous policies were the result.

Again we have a case of a system dominated by a minority (the so-called 1%—in reality, the top 10%), that catered to a minority, the 2% who were most vulnerable. The rest, the 98% would barely be affected, if at all, by the virus—and thus all the measures and the vaccines are unnecessary. Vast sums of money have been wasted.

Sloot’s final message is to the point: “We must stop this right now and get back to normal”.

Concluding Assessment

This is another documentary where the presenter is an “actor” within the presentation, and I really welcomed having Nico Sloot act as our tour guide, lead questioner, explorer, and advocate. His self-presentation can vary from innocent, vulnerable, and dumbfounded, to inquisitive, incisive, and critical.

Surprisingly beautiful was the cinematography that draws in viewers and sustains attention. However, something was at work here, I suspect: Holland is shown as an almost picture-perfect postcard of a country, with lovely homes, artistic architecture, cooling green countryside, and a deep dark ocean. In a way then it visually suggests what is at risk, what is at stake, and what is worth defending. This kind of filming achieves, in a very subtle way, a reaffirmation of our sensations of the deep tragedy of the past year, and everything that was grim, suspicious, and tense about this lockdown experience. Indeed, a brief succession of footage stands as a painful reminder of the ghastly atmosphere of this ongoing situation.

The filming is serene and calm, which also means there are long pauses between different people speaking so that ideas, information, observations, and reflections can properly sink in. During these pauses, long, slow, rolling scenes of urban landscape unfold. Unless Nico is meeting with an individual, or a group of people, he is shown totally alone in the cityscape, reminding us of the melancholy and sometimes the sheer desolation we experienced.

Participants in multiple dialogues in this film (made during the height of the “pandemic”), are shown speaking in close quarters: on a shared sofa, at a table, walking side by side in a park, etc. Nobody in the film is ever masked. The filming itself defies fear.

It is an elegantly done film, but to be clear it is also a simple construction. The film consists of people conversing, making very intelligent, incisive, and thought-provoking points. Yes, this film could well be used in a university classroom setting (it won’t be though, it rubs too much against the grain of elitist ideology), but in such a setting it should be used primarily to stoke discussion and debate, to form questions, and a teacher would need to bring in additional, complementary resources to deepen what is said in the film.

This film could/should be used in any university course that either wholly or partly incorporates study of “the pandemic”. One could see this film being relevant to courses in Communications, Public Administration, Political Science, Psychology, Economics, Sociology, or Anthropology. Personally, I am asking my university library to order it so that I can use it in the next delivery of my Political Anthropology course.

What impresses me is that this was not just a collection of opinions, instead it brought forward the kind of historical and scientific information that was neglected or sidelined over this past year. In addition, rather than just disjointed interpretive remarks, this film goes to some length to provide a basic and efficient theoretical analysis, on which one can build. This was perhaps one of the benefits of having some key academics participating in Sloot’s project.

A few negative reviews have been posted to IMDB, but they in no way reflect the actual contents of this film. Instead, they seem to be motivated by a knee-jerk political reaction, or even just hysteria and fear, thus leading some to misrepresent the film as one spreading “misinformation” (presumably because “the science” as always is “settled,” and total consensus reigns). To say that “on YouTube you would be booted off,” may not only be a repulsive sucking up to the power of Big Tech, it could also be an example of the steadfast ignorance that has ruled/ruined so many, thus proving precisely why this film is very much needed.

Overall, I genuinely appreciated this film and sympathized with its main speakers and their arguments. I feel compelled to rate this film 8.5/10.